David Sasaki’s Time Capsule piece, When Languages Die, Part 2, triggered something deep within me. His reflections on the quiet extinction of languages across the globe took me back to my own childhood in Kenya, where speaking your mother tongue was frowned upon—where the sound of Gikuyu or Kamba in a schoolyard could summon a teacher’s scolding or worse. It reminded me of how, as children, we were taught to aspire to sophistication through English or French while our native languages were relegated to the realm of the uneducated and unsophisticated. What I didn’t understand then but see clearly now is that this wasn’t an accident. It was part of a larger, deliberate project to strip us of our identities, and I fear AI could complete the job.

Artificial intelligence, that dazzling promise of a smarter future, carries a darker edge. Built on vast datasets dominated by global languages—English, Chinese, Spanish—it has little room for the languages many of us grew up hearing around us: Gikuyu, Shona, Baganda, Kichaga, etc. These languages, rich with stories, philosophies, and wisdom, are teetering on the edge of extinction, if one takes a long-ish term view. As I consider how AI might play a role in this erosion, I cannot help but ask: is this the final chapter of a neocolonial order, a digital completion of the cultural erasure begun centuries ago?

Colonialism’s Grip on Language and Identity

Colonialism wasn’t just about conquering land; it was about reshaping minds. European powers understood that to dominate a people, you must dominate their language. In Kenya, as in much of Africa, children were punished for speaking their native tongues. In schools where success was tied to English or French, languages like Gikuyu and Luo were silenced and dismissed as primitive relics. This wasn’t just linguistic suppression—it was a severing of connection to culture, community, and identity.

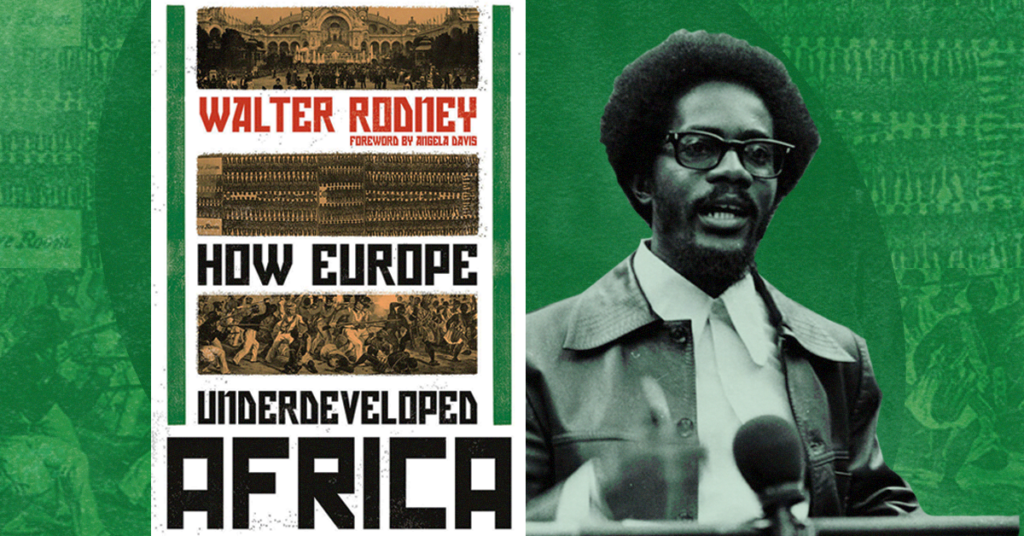

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o captures this beautifully in his book, Decolonising the Mind: “The choice of language and the use to which language is put is central to a people’s definition of themselves.” Colonial powers understood this truth, weaponising language to break our spirits. In How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney added another dimension to this dynamic. Colonial education, he argued, wasn’t designed to empower—it was designed to create obedient workers, fluent enough to serve colonial economies but not enough to challenge their foundations.

This project of cultural domination lives on. Our schools, even today, hold tight to Eurocentric curricula. I think of the Kenyan elite schools that boast global standards, teaching students about European monarchs, American presidents, and “global history”, which really means European and American History, while African heroes like Patrice Lumumba, Wangari Maathai, or Thomas Sankara remain footnotes. These institutions, celebrated as “premium,” still reflect the colonial mindset that our history and our languages are not enough.

Not Much Has Changed: Colonial Elitism in Education

The colonial legacy is glaring in many of our institutions, particularly elite schools, which remain steeped in practices and structures that reflect colonial ideals. As Prof. Wandia Njoya highlights in her insightful piece, “2-6-3-3: Colonial Elitism in Kenya’s Education Continues,” Kenya’s education system remains tethered to its colonial roots. She recounts her experiences during the transition to the 8-4-4 curriculum, observing how it was met with disdain by those educated under the earlier A-level system. This disdain, she argues, reflected a lingering colonial snobbery among older generations who were taught by white missionaries and internalised the superiority of European-style education.

Prof. Njoya also critiques the ethnic diversification of schools through the quota system introduced under President Moi. While this system aimed to promote inclusivity, it failed to address the deeper issues of elitism and inequality entrenched in the system. Schools continued to prioritise Western knowledge and languages, sidelining African history and culture. These attitudes endure, fostering the perception that education rooted in African traditions is of lesser value, further marginalising indigenous knowledge systems.

I have also written how things in Kenyan prisons are still the same in custom and form – even now in the 21st Century!

The Personal Cost of Cultural Inferiority

Growing up, I didn’t question it. Speaking English was aspirational; it meant you belonged. Speaking Gikuyu, Giriama, Kitaita or Kiswahili? That was for the unsophisticated. It wasn’t just a school rule—it was an unspoken societal contract. To succeed, to rise, you had to leave your language and, by extension, parts of yourself, behind. As a child, I didn’t see this for what it was: a form of indoctrination, teaching us to see ourselves through the eyes of our colonisers.

Today, that same cultural inferiority complex is being mirrored in the digital age. Artificial intelligence systems, those marvels of innovation, are overwhelmingly trained on dominant global languages. The algorithms that power tools like ChatGPT or Bard don’t have room for Gikuyu or Shona, unless someone is willing to invest in building datasets, lexicons, and linguistic rules. But who will invest in a language that the world has been taught to undervalue? The danger is clear: AI could finish what colonial education began, making these languages not just marginalised but obsolete.

AI and the Digital Divide

George Orwell’s 1984 warned us about the power of language—or the lack of it. In his dystopian world, Newspeak, a language engineered to reduce expression, was a tool of control. Today, AI-driven linguistic hierarchies echo this chilling warning. By privileging a handful of dominant languages, AI systems risk narrowing the scope of human thought and cultural diversity. Speakers of minority languages may feel compelled to adopt dominant ones, not just for economic survival but to participate in the digital world. What begins as a convenience could end as a cultural erasure.

This isn’t just about technology—it’s about geopolitics. The dominance of English in AI reflects a larger power dynamic. China’s Belt and Road Initiative promotes Mandarin as a global language of commerce and diplomacy, while Western tech giants cement English as the lingua franca of AI. Meanwhile, African languages remain on the periphery, excluded from the digital future.

Resistance Through Multiculturalism and Education

But I am not without hope. Resistance is alive in the movements and initiatives that seek to reclaim and celebrate our languages and cultures. In Kenya, Kiama Kia Ma stands as a testament to this resistance, reviving indigenous governance and cultural practices. Across Africa, universities and schools are integrating African history and literature into their curricula, introducing students to pre-colonial empires like Mali and Great Zimbabwe and figures like Thomas Sankara and Wangari Maathai.

Technology, too, can be a tool for preservation. At the intersection of education and technology lies a powerful opportunity for cultural preservation. While AI and digital tools often threaten linguistic diversity, they can also be harnessed to revitalise endangered languages and amplify African voices. Platforms like Masakhane and Sunbird at Makerere are creating open-source datasets for African languages, integrating them into AI systems to ensure their relevance in the digital age. These initiatives demonstrate that technology need not be a tool of erasure but can instead bridge the gap between tradition and modernity.

Redefining “premium” education

Equally important is the growing movement to redefine “premium” education, challenging the idea that global curricula centred on Western knowledge are inherently superior. Schools that teach African history, literature, and languages are increasingly seen as institutions of excellence, offering students a holistic education that affirms their cultural roots while preparing them for the global stage. Together, these shifts in education represent a profound act of resistance—one that ensures Africa’s diverse voices and stories remain vibrant and enduring. These efforts remind us that while technology can be a threat, it can also be a tool for empowerment.

Education has always been a battleground for identity, and across Africa, it is increasingly being reclaimed as a tool of resistance and cultural revival. A growing movement is challenging the long-held dominance of Eurocentric curricula by integrating indigenous languages, histories, and narratives into the fabric of learning. In Tanzania, for example, the late Julius Nyerere championed Swahili as the medium of instruction, recognising that education in a familiar language not only fosters deeper learning but also affirms cultural identity. Though implementation has been uneven, it remains a landmark step toward reclaiming linguistic agency. Similarly, UNESCO and other organisations advocate for mother-tongue education as a way to improve learning outcomes while preserving endangered languages. These efforts directly counter the colonial legacy that sought to erase African languages from formal education systems, reminding us that language is both a vessel for knowledge and a source of pride.

Reclaiming Africanness

Beyond language, there is a concerted effort to reclaim African history and place it at the centre of education. Across the continent, schools and universities are revisiting curricula to highlight the achievements of African leaders, thinkers, and civilisations. Figures like Patrice Lumumba, Wangari Maathai, and Thomas Sankara are no longer marginalised as mere footnotes but are celebrated as icons of resilience and justice. Pre-colonial kingdoms such as Mali, Songhai, and Great Zimbabwe are being reintroduced to emphasise Africa’s historical contributions to global knowledge. Initiatives like the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and platforms such as the Afrocentric School aim to inspire pride and belonging in young Africans, challenging the perception that true education must revolve around European or American paradigms. By embracing these narratives, these programmes not only decolonise knowledge but also equip students with the confidence to shape their futures.

The stakes are high. Languages like Gikuyu, Shona, Baganda, and Kichaga are more than just words—they are vessels of identity, memory, and worldview. If these languages disappear, it is not just a cultural loss but a human one. AI, with its immense power, could either hasten their decline or become a force for their revival. The choice lies with us.

We must fight for an inclusive digital future where every language has a place. Governments must invest in the digitisation of indigenous languages. Educators must decolonise curricula to prioritise African knowledge and history. And technologists must recognise the value of linguistic diversity, building tools that reflect the richness of human culture.

As I reflect on my own experiences and the lessons of history, one thing is clear: this is a battle for our identity, our heritage, and our future. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o said it best: “To starve or kill a language is to starve and kill a people’s memory bank.” Let us ensure that our memory banks are not erased but enriched, and that the languages of Africa remain vibrant voices in the global conversation.

The time to act is now.