By Al Kags

(First Published in the Standard)

Nairobi — Despite the encouraging news about improved conditions, Kenyan prisons still have a long way to go. This verbatim account narrated to AL KAGS by an inmate who spent 12 days in the Industrial Area remand prison, Nairobi, explains why.

“1911. Kenya Prison Industrial Area”

Inscribed at the entrance to the Industrial Area Minimum Security Prison nearly a century ago, these words remains defiantly legible. We drove into the imposing gate of the prison at 5.30pm on January 9 in a dark green Maria with a metal-sheet panelled chassis except for small lofty meshed window.

I stood at the back of the lorry along with the other ‘inmates’, our hands barely managing to hold on to the window mesh for support. If I think of it, I doubt that I could have fallen even if I held on to nothing; we were so deftly packed that one could not move an inch. The whole atmosphere in the back of that lorry – a smelly, sweaty, dirty conglomeration of arms, legs and bodies of various builds – still sends shivers down my spine.

We alighted under tight security and were hurriedly prodded, pushed and pulled into a small compound made of concrete slabs. Looking around me, the word “colonial” sprung quickly to mind. Orders were barked and there was more prodding and shoving by officers in differing uniforms – some in the standard prison uniform (light brown top and trouser with a green belt and black boots) and others in jungle green combat jackets and greenish brown trousers and boots.

I found that we were to be sorted and counted and I quickly learnt the meaning of a new word: “Kapa.” It reminded me of Pavlov training his dog and discussing conditioning thereafter. So there we squatted in several rows, five men to a row, to enable the warders perform a headcount.

Remand section

We, the inmates, were from court, and had to be separated at that point. Those who had been found guilty and sentenced were to go to the prison side of the complex and those whose trials were still pending were to be shown to the remand section. I belonged to the latter group. We were sorted in these categories from the records, which again made it clear that many of these warders still had issues with reading and writing.

After the complex sorting exercise, we were herded into the main compound and activity area of the prison. A burly and very smartly dressed officer was there to meet and welcome us. Obviously he was of some higher rank than the rest. He was very composed and almost seemed nonchalant – like he had done this very often and he was going to say and do the same things he has said and done over and over.

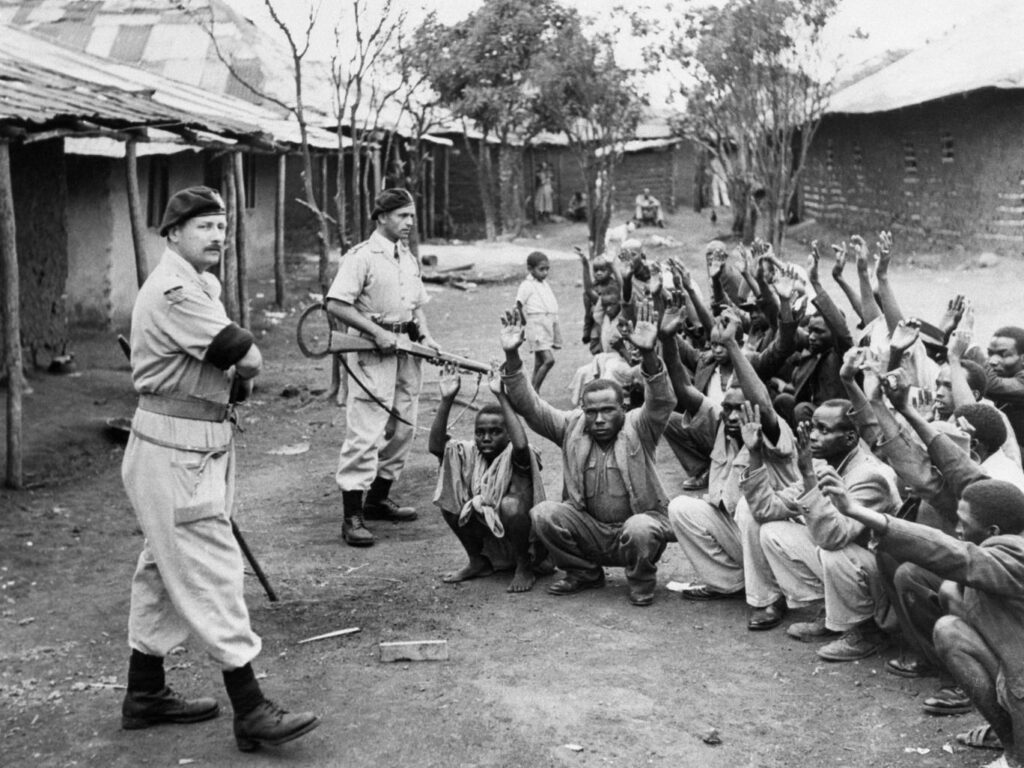

The treatment of prisoners is reminiscent of the treatment of Mau Mau prisoners in the 1950s.

The officer asked us to “kaa kama mabusu” (sit like prisoners) – Kapa! As before, we squatted in rows of five men each. The new lesson regarding this manoeuvre is that it has to be done with the maximum of speed. A slow man would be encouraged with a blow or two.

I doubt the welcoming officer (he did not introduce himself) would have had any significant impact in my memory except when he clearly stated that “mambo ya jela hayawezi kubadilika” – that the age old practices of jail cannot change. He reminded us that the Industrial Area Prison was erected in 1911 and, as we must have heard outside, not much has changed in terms of conditions and practices. He talked of the food, how inmates are handled, and the general concepts of human rights as a waste of time and energy for us to try and nose about. So we knew about the horrible food, poor sanitation and mistreatment of inmates by warders.

Who were we to change anything that no one has bothered about since 1911? He posed the question and fell theatrically silent – to allow us to ponder over and let it sink. The officer then admonished us to concentrate on our pending cases – of complainants and witnesses and attending court as required.

It was about 7:30pm when we were moved to the remand halls. I was shown into J8, a large rectangular hall with mattresses – or more accurately some semblance of bedding arranged everywhere. A cop standing by the open heavy metal door guarded the people. When I eventually walked in, I did not realise that I would not see the sun again for nine days.

When things finally settled down, I began to examine my new surroundings. Sure, there was life in the room but one would be more accurate to call it that. Here was humanity trying to survive. There were about 150 men in the room; some were asleep, some all smiles and seemingly comfortable, and still some all too obviously mentally unsound. It was clear that most of the residents were at some stage of one disease or another. Space was definitely an issue.

I had read in the press that things were a lot better in the Kenyan prison. The Minister in charge of the prisons, fondly called Uncle Moody, had delivered thousands of beddings to prisons around the country. We watched news about new mattresses and beddings, and even a television set, delivered to the prison and we were assured that the same was done in prisons across the country.

I found very old pieces of blankets and worn-out mattresses as thick as foolscaps were scattered around the room. Indeed, the floor was bed for many.

I was to quickly discover that there is thriving commerce in remand. Whatever little there was in the remand cell (hall is more like it) was for sale. I was quick to learn that with money one can live a very nice and comfortable (sic!) life in a GK prison.

According to prison rules, to have possession of money is illegal in there. But there is a well-co-ordinated money trade that goes on inside the prison. There is a system to things. Since money is necessary to have in there, it is smuggled in with the help of the guards. They take 25 per cent of whatever amount is brought for the prisoner by his relatives outside. The money is handed over by the guards to the senior inmates who, less their levy, hand it over to the prisoner. Some-times the prisoner receives no money at all.

The money is used primarily to get better food from the kitchen in the evenings. For Sh50 or Sh100, one gets a good quantity of better quality food smuggled in from the kitchen by the prisoners who work there. In addition, because of the scarce bedding, most inmates get to sleep on the bare floor. To sleep on the threadbare mattresses – in the area called “state house” – one needs to cough about Sh1,500 and you have it for the entire time you are there or you could rent it at about Sh100 or so a day.

One learns before too long how to get money smuggled in and how to hoard or hide it and buy special food from the kitchen.

Rude awakening

I had hardly settled in when some of the men, all well built and obviously familiar with the system, demanded to have my spectacles. Interestingly, they immediately began to hassle over who among them deserved to have the spectacles. It was escalating to a full-blown war. Not wanting to be involved in the brawl, I handed the glasses over to one of the men who put it on immediately – and then quickly removed them in shock. I happen to have very bad eyesight and my specs are of high specification. It is painful for a person of normal eyesight to keep them on. They were returned to me immediately and no more interest was shown in me.

Sanitation

There was an awful smell in the air and I recognised it from my earlier sojourn at the Kilimani Police station cells. It was the miasma of stale urine, body sweat, an unattended toilet and dirt. Since I was pressed to relieve myself, I walked in the direction of the stench.

I ended up in a room that had about four toilets and a broad sink. Pools of water or urine were all over the floor. I tried my best to walk on the dry spots on the floor knowing fully well that this was the war-zone of disease. The mess got worse with every step I made closer to it. The moment I walked into the loo, my urgent need to relieve myself vanished.

I found the sewerage system must be obsolete or non-existent in the room. I later learnt that water was extremely scarce in Industrial Area prison and in other prisons as well. Cholera, dysentery and other stomach based diseases were commonplace here. Such was the shock to my system that I never once felt the urge to relieve myself. I wondered what happens to those who have to be in remand for months and even years. Do they have some sort of switch-off mechanism that allows them to preserve themselves or perhaps they acquire the strength to ignore the abominable environment enough to do their thing?

No medical attention

I remember an incident that happened while I was there: There was a man, about 6ft tall and very slim who had been sick for about five days. His absence from “Kapa” was noticeable. He was curled under his blankets most of that time, sick and hopeless. On this particular evening, he was found in the toilets face on the dirt and in the puddles having very strong seizures. We dragged him back to “bed” and tried to keep him warm. At the same time we yelled for the warders to come over and help.

We called and banged on the door, “Afande! Afande! Mtu anakufa hapa! Saidia”! (Warder! Help! Someone is dying here!). The men in other cells heard our cries for help and joined in. For 30 minutes we called in a united bid to save a life – all 600 or so of us on two floors of the building. I have never heard such a racket in my life.

Eventually, a corporal swung the door open and found us huddled around the dying inmate.

“Mnataka nifanye nini” (What do you want me to do)? he sneeringly asked. “Take him to hospital,” someone replied. He looked at us with a disgusted look on his face and left. Much later, he commissioned four men to carry him out. Rumour has it that he died that night.

About three people died of congestion and illness every day I was there.

There is a news-mill much like the rumour mill of Nairobi that lets inmates of both remand and the prison know about these incidences. News of a death always flew about when it happened. Most of the deaths happen in prison where the convicted felons are kept not in remand.

I firmly believe now that he that sends you to a Kenyan prison is in fact condemning you to die surely, gradually and most painfully. There is no such thing as rehabilitation. The notion that one is presumed innocent until proven guilty is not in practice. This was remand not prison.

That first night I spent crouched by the wall, not sleeping, just watching. I stayed awake most nights with short periods of disturbed dozing until sometime early in the morning, when a bell would sound. We all would arise and rush to “Kapa”.

Typical Morning

The morning “Kapa” session is as interesting as it is chaotic. A stampede ensues at the sound of the bell as all prisoners in the room rush to squat in their place. Many fall and are trampled in the rush. The men are all shouting at the top of their voices at the same time and it is a confused and panicky environment to be in at the time. In less than a minute, though, everyone is in position and at “Kapa”. The sile-nce once the rows of five are complete is palpable.

Prayers usually followed the Kapa session. Several men loudly shout their prayers asking God to come to their rescue, as if to ensure that their prayers get out of the mostly unventilated room. They sing and clap vigorously with bold and selfless faith early in the morning before falling to their knees and offering their heart-rending prayers.

I once shed a tear in observing the seemingly very sincere manner in which they called upon a father that is not seen. I am sure that if I was God, I would grant their wishes quickly considering how moving the whole scene was.

Many men cry early in the morning. It may be the realisation that morning has come and they are in gaol – that it is not a dream.

Food

Breakfast is always porridge without sugar. The porridge is very light and lumpy and it was always undercooked. We queued in long lines and waited for our turns to be served. Somewhere along the line, one is handed a metal container that looks like it can carry a healthy serving of a meal. My hopes for a good amount of porridge were dashed on the first day after a tiny amount was poured into my metal container. One finds oneself nursing the little porridge with a lot of care and attention.

Lunch is ugali and vegetables or ugali with beans. The ugali is just porridge left to harden and it is lumpy and uncooked. I hear that it is cooked partly with the brawn that is a by-product of maize milling. One can taste it and see it in the uncooked lumps. Nonetheless we ate; it was that or death from starvation.