Throughout this electioneering period I have remained generally silent. I have allowed this blog to go quiet and I have generally kept my views to myself. In matters politics, I have strived to maintain a balanced stance within myself – and in these partisan times, that is crazy difficult .

However, I am resolute that I will speak only about development issues, the wellbeing of our country, Kenya, in practical and policy terms.

One of the major reflections that I have had these past couple of weeks has been just how difficult it is to remain non-partisan in a highly polarized environment, such as the one we are living in today. People feel very strongly on political issues and personalities along very distinct lines. Even the notions of peace and justice have become highly contentious in today’s Kenya. See my Facebook post below and take a moment to sample the reactions therein:

This is not to say that I do not have political views, however. I do. Its just that my views will not gel with either side in Kenya’s peculiar political division. I work hard to see both sides of the coin and to stop myself from falling into the propaganda trap that tends to obfuscate the real issues. I work hard not to assign too much importance to the personalities involved, safe in the knowledge that their political positions, alliances and competitions are transient and temporary.

This is what all the people and organisations that are non-partisan are called to do. Religious organisations, the security services (lately they are forces in Kenya), judicial officials and many non-profit organisations have to pursue objectivity above all else – and that is no small feat. Take the church for example. In Kenya today, the church is as divided as the country with clergy taking partisan views to the pulpit – in central Kenya we have seen pastors even go on radio to portray their candidate (the president) as holy and “Ordained by God” and in the same breath speak of the opposition as “of the devil”. The other side has not been much better. See the banner below: “Raila, Baba, Mwana na Roho Mtakatifu” (Raila, the father, son & holy spirit), it says, “We have the right to worship anyone. What is wrong with calling Baba (Kenya’s sometimes affectionate name for Raila Odinga) our God?”

Here’s the thing. It is my view that in doing so, the church has not only abdicated its position as a moral guide to the society but as an entity charged to market God and his son, Jesus, also does a lot to push people even further away. See, if the church is not seen to be at the pinnacle of the moral pedestal, if it cannot stay above the fray, then it reduces its authority – and God for whom it speaks. The unfortunate thing is that the church, in its general fragmentation, is not known for its course correction. A few years ago, the main story in the news was of rogue pastors and preachers who cooked up improbable schemes to get people to give them money. No sanctions from anywhere and no “legitimate” churches spoke out to call out the “false prophets” as they were.

Today, institutions that are required to be non-partisan must stand and speak truth – and it has to be objective truth. The organisation that I lead will strive to do so as long as we are here.

So what are the issues as I see them?

First, development has been too unequally distributed in Kenya since independence. This is the heart of the justice discussion. If you look the data you notice that whereas there are 5.2 hospitals per population of 10,000 in Nyeri, there are only 1.2 for a similar population in Kisumu. There are 25 health professionals in Nairobi per 10,000 and only 3 in Mandera.

Above: locations of secondary schools in Kenya – not much difference in the past 10 years

Secondly, the gap between the rich and the poor has steadily increased and life has become increasingly untenable for most Kenyans. Income inequality is a real concern in Kenya. According to the Society for International Development, this publication shows that the country’s top 10% households control 42% of total income while the bottom 10% control less than 1%. According to the Human Development Index 2014, the incomes of the richest 20 per cent of the population rose steadily in the past decade to stand at 11 times more than the incomes of the poorest 20 per cent.

The challenge is that there has not been a framework in place for Kenyans to discuss this very emotive subject. Even the politicians as they discuss the haves and have-nots don’t go there, instead finding scapegoats in the “other tribe”. I have talked about this with several people lately and one said to me, “the day we talk about the real two tribes in Kenya – the poor vs the rich, none of us will recover from that explosion.”

Third, wealth creation and control has been too intricately tied to politics. Politics is not a calling in Kenya — it is the route to wealth. It is generally agreed that it is mainly because of Jomo Kenyatta’s presidency that his family is possibly the richest in Kenya today, closely followed by that of the second president, Daniel arap Moi. It is known that many “old money families” became so because of the patronage of these presidents. They include the first vice-president Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s family, the former Central Bank governor Philip Ndegwa’s family, many ministers and public servants over the years. Even today, we have seen people’s fortunes change dramatically in a matter of a few years after getting elected or nominated to various offices of public service. Many of those jobs are plush, low-stress-requirement jobs.

It is this pursuit of political power and patronage that drives the political divide. The politicians must control the resources and allocate the public purse in a way to benefit them and theirs. The public thinks that the politicians will provide the patronage benefits that will trickle down to their villages and marketplaces.

Most importantly as far as I am concerned, Kenya does not have a lasting competitiveness philosophy. (to understand competitiveness, maybe start by reading this and watching this video of Michael Porter explaining it)

Looking at Kenya from a global perspective, we have allowed ourselves to be distracted from a long term competitiveness platform — one that looks at the global dynamics and positions the country to have and maintain a unique value proposition. This is the one thing that most giants that have rapidly grown share — from Rwanda to Dubai to Singapore and Malaysia etc. We have not answered the question: what do we want to be unique for in a globalized world? What is the one thing that we can produce that the whole world could come to us for? That is what competitiveness means.

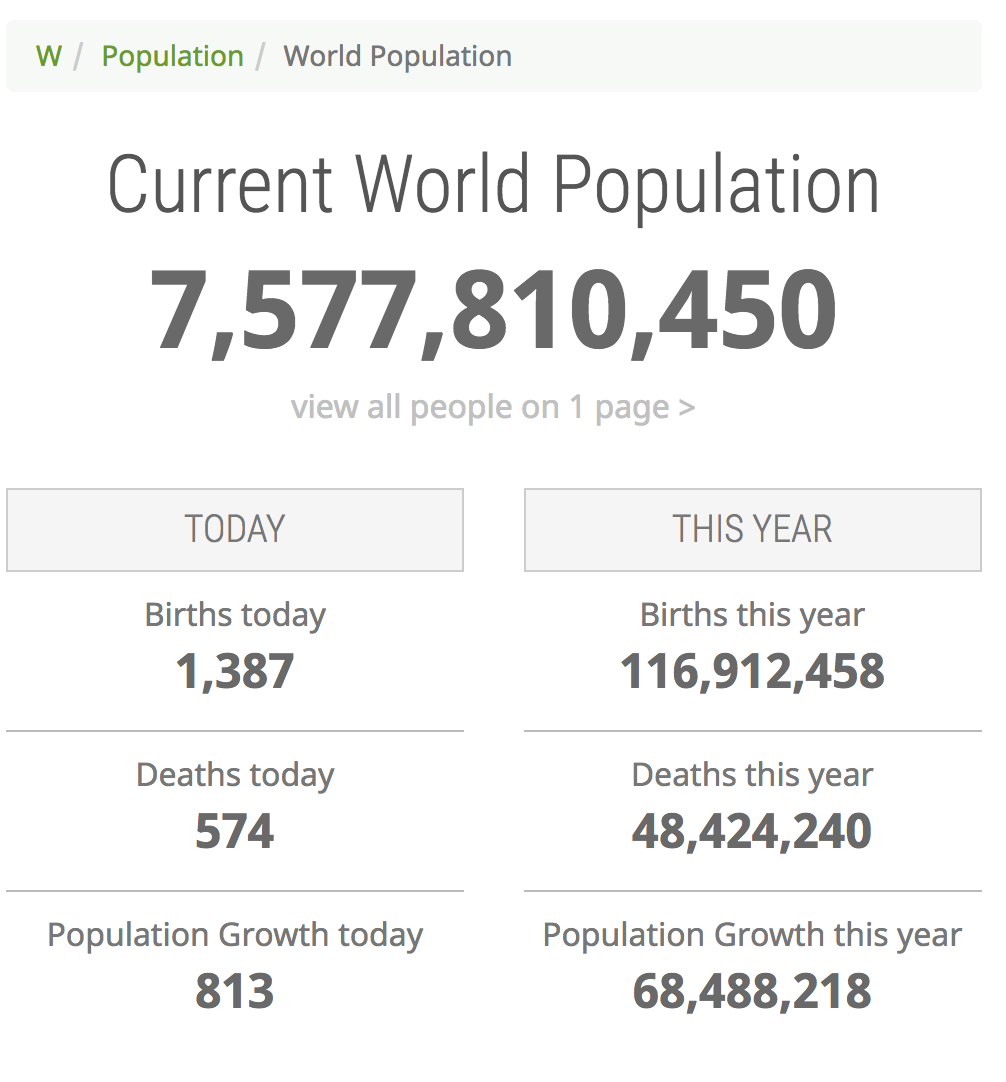

Here’s the world’s population as at 12.05am (East African Time) on October 31st 2017. If you would like to see the world’s population as at the time you are reading this, go here. By mid 2030, we are expected to hit 8.4 Billion people.

Today, approximately 4,092,017,643 (more than 4 Billion people) live in urban places. By 2030 the world is going to have at least 41 cities in which more than 10,000,000 (Ten million) people live – and Nairobi will be one such city with about 14.3 Million people in 2030. Most countries will have a higher population than they can feed. Who will feed all this people?

A Competitiveness Philosophy could be that Kenya organises itself to be the world’s food basket by 2030 – that would mean policies that slow down the rate of farm breakdown in fertile lands, increase of productivity in places like Nyanza, Coast and Rift Valley and the turnaround of the drylands of the north to fertile food production land. It means developing protectionist policies that halt the importation of foodstuff from other countries (can you believe that you can eat fish from China in Kisumu?). It means developing policies and incentives that support food processing in Kenya – ensure that Kenya is a net exporter of processed sugar, salt, maize and rice by 2025. It means we trade off other industries that may not do as well.

Hey, I am not in any way suggesting that food is our ultimate competitive strategy. But I am suggesting that Kenya has to congregate itself around one, fast.

I am suggesting that the government organises itself to administer social justice quickly – focus more (both politically and practically) on the marginalised parts of Kenya. Let the president physically situate himself in those counties that have been marginalised for a month and work with the people there on a development plan for those county clusters and let the citizen drive the agenda. Let us see more hospitals and schools not just roads and electricity. Let us see more industries in those counties stimulated by the government.

I am suggesting that there are many people who feel disenfranchised and apart from listening to them, serving them in a meaningful way is a valuable way to go. Ultimately, we all have to find the objective centre of our hearts and talk soberly about what is really important.