“It could be worse,” said my grandfather.

This article was first published in my Standard Column on Friday, April 17, 2020

This week, having spent the last few weeks with my wife, children, my mother and stepfather, it was decided that we must take on a project for my stepfather to do. The poor old man has been accustomed to working with his hands and never being idle, even after retiring in the past decade or so. He is known to always be tinkering with wood, nails and assorted tools fixing this or that, and now, he had to simply sit still for most of the day.

Several kilometres away, in Kiambu county (but within the Nairobi metropolitan area), my octogenarian grandfather was driving my grandmother crazy because he had decided that he was going to go back to work. Considerably weaker than he used to be, the old fellow has lived the motto that if you are alive you must “do something” and in recent years that “something” has involved tending a small shop where he sells paraffin at the corner of a busy road.

It was agreed as a family that it was good for him to have the shop, not so much because he makes much money from it – in fact, we all doubt that he turns a profit from it at all, but because it allowed him a sense of purpose. By having the shop, the mzee is able to “go to work” and meet with other people and perhaps ruminate over the good old days with his pals sitting on stools outside his shop.

Now suddenly, these two old men had found themselves forced to stay in the confines of home – one dosing in a peaceful farm cottage surrounded by trees, flowers and deafening silence most of the day, and the other in his step-son’s house forlornly watching documentaries on a computer screen, with only his grandchildren to distract him sometimes. They are both in the higher risk category of the population and as a result, we had encouraged them strongly to stay indoors.

Such is the impact of this virus and the resultant radical measures that the enviable Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe and his team have had to put in place. As many people focus on following the stringent regulations that have been placed upon all of us, the mental health of many people is thoroughly tested. Even younger people are not spared the strain as we have started to see on social media young people saying, “kama mbaya, mbaya” as they leave their homes to go visit others or worse, as they congregated in a car park in Langata to libate and “hang out” with their contemporaries.

We, therefore, created a project for the old men – to work together build a wooden shed in the backyard – one that I would vainly like to call a gazebo to shield us from the sun as we sit outside the house. Happily, they set about the task with great enthusiasm only stopping when they had run out of supplies or to eat and replenish their strength.

It could be worse

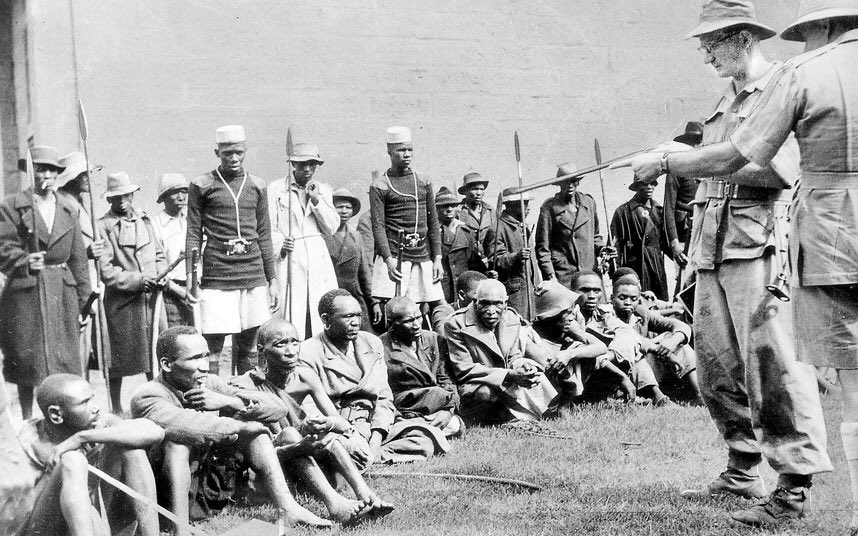

“It could be worse, you know,” said my grandfather during one of his rest stops. “During the emergency days in the fifties, we saw much worse.” He went on to tell me that back in 1953, when he was about 19, Africans were not allowed to leave their homesteads (a generous term to describe a haphazard collection of mud huts in a corner of a white settler’s farm) without permission or direction from either the white man or his homeguards.

Home guards were African loyalists who were placed to be in charge of keeping the natives in check and gather intelligence about possible Mau Mau sympathisers. Their perks were dependent on how they plied the “mubeberu” a steady stream of actionable intelligence on the comings and goings of their fellow natives as well as their enthusiasm for “maintaining order” – usually by brutally beating Africans within inches of their lives.

“Those beatings that I saw on TV when the police were beating people for being out after curfew- that was nothing,” Mzee told me wistfully. “You see, that was just a normal beating that you would get from a home guard because you passed him and he didn’t hear you say hello to him.”

In those days, there were three people to watch and be afraid of. First was the homeguards who would deliver broken bones and permanent injuries at the slightest provocation. Then there were the Christian converts, who would tell on you to the settlers as a means of ingratiating themselves. Finally, you needed to watch out for the Mau Mau – especially the low key members who lived in the reserves with everyone else, but who could report you to the Mau Mau for being a traitor.

While these stay at home regulations are hard on the mind, my grandfather said that it was important that we thank God that it is not worse and that we should always try to see the brighter side of things.

“I think I would tell you to start to observe just how important it is that you live in a place where ordinarily you can go where you want and do what you want without fear,” Mzee told me. “There was a time when you would not have been considered more valuable than a goat or a donkey that ploughs the field – and at that time you would be treated like you are one.”