Of blogging and how past practices could be useful in making a happy future.

I have lately been encouraging many members of my staff to start blogging and to make it a habit to demonstrate their growth by simply documenting the lessons they learn through their various experiences – at work, at home and elsewhere.

Many of them are timid about writing and expressing themselves, mainly because they feel that while they speak the language, their thoughts are not of good enough quality to be expressed publicly, or that their language is not developed enough for them to share their thoughts.

“Expose your stupidity” is a mantra that I have often used to tell them to be confident enough to start blogging – the finess comes with practice. I have enjoyed to see a couple of them start doing so. Follow Frasia Kamau and Oliver Kagwe to see how they develop their space over time. And if you are one of those people who worry about starting a blog, I can think of no better encouragement than Oliver’s maiden blogpost.

One of my newest mentees, Wangari Kimani, challenged me to write about what I think of traditional practices past that could be invaluable in the future and what I thought the impact would be. I accepted the challenge.

Of traditions and the future…

It has been my long held belief that the past has a great impact on the future. Recently for example, I was speaking with my best friend about the challenges of bringing up children and the necessities of presence. In that conversation, he told me about a parenting class he had attended in which the facilitator mentioned that we often have the right intentions as parents but the effect is lost in translation.

Think for example about a parent who wants his child to do well in school but is overly critical of the child – in some cases to the point of beating the child for say, not getting the best grades. The lack of affirmation has an impact that is visible in many people of our generation – we are afraid of failure and so we do not try. When we do fail, we work hard to cover up our blunders.

It occurred to me in the conversation that the fact of the matter is that many of us as parents have not had a chance to examine just how damaged we are and what part of that damage we pass on to our kids. I recognise that the process of discovering our personal damage requires us to review how we grow up and eventually to take a good long look at our parents as “John”, “Mary”, “Abdul”, “Faiza” or <*insert your parents’ names*> as opposed to “Mummy” or “Daddy”. That way, we see how they arrived at being the parents they were and how they ended up making the mistakes they did with us, despite loving us and wanting the best for us. What that does is that it enables us to forgive and put our own upbringing into perspective. We decide what parts of there practices we shall break with our future generations.

What I think I am saying is that connecting with the past and putting it in perspective would have a humongous impact on our future.

Some of the old traditions that I would love to see more of and that I think will be of particular use to the future generations are:

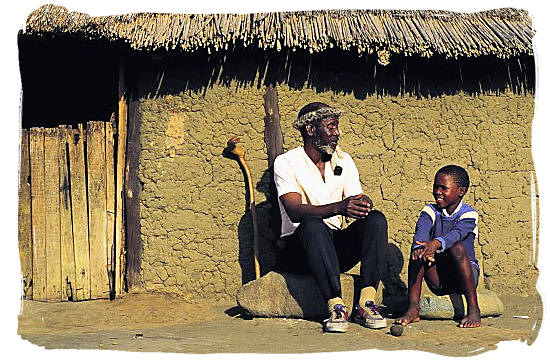

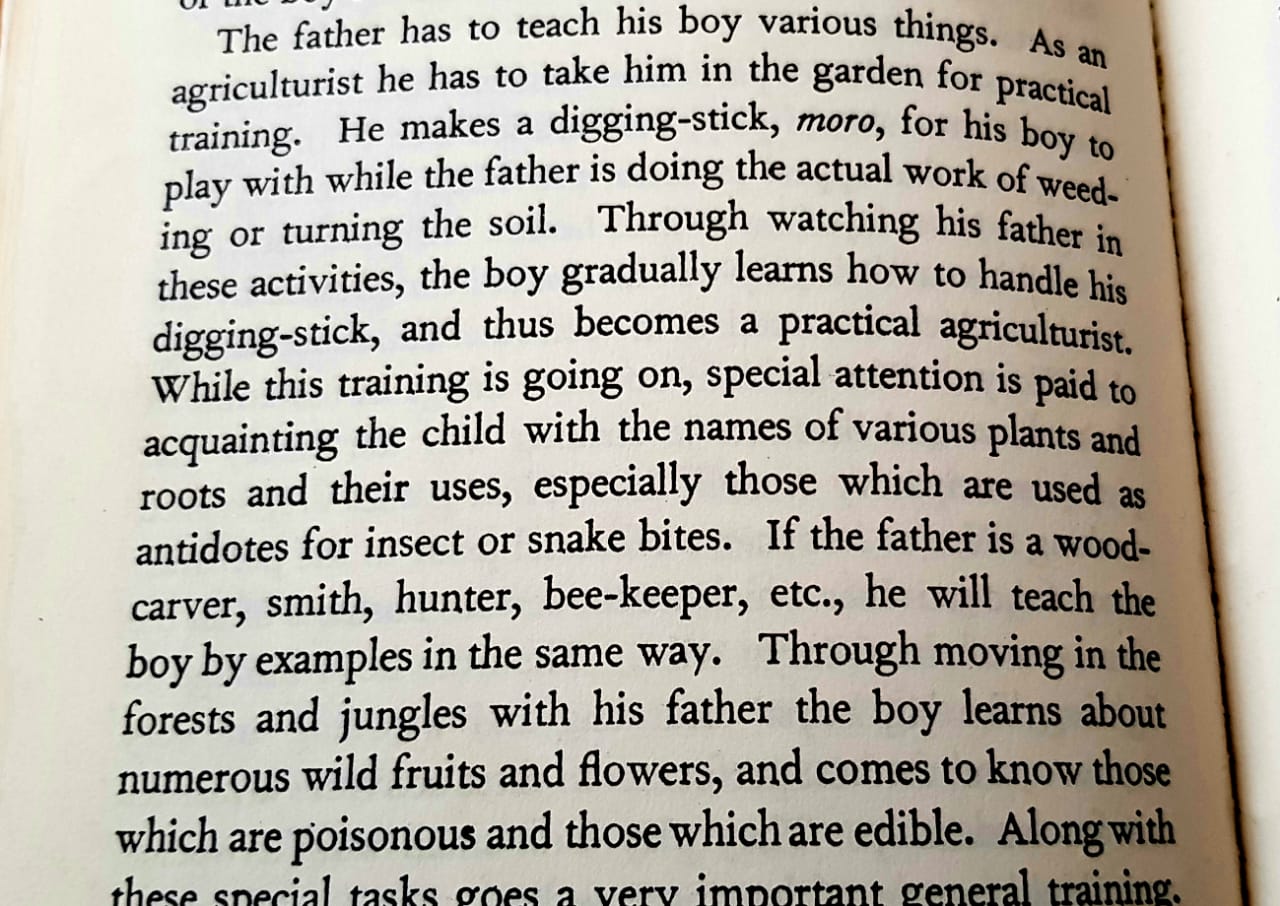

- Greater mentorship: In the old days, in just about all African traditions, there was a deliberate effort to pass on ancient knowledge and practice from one generation to the other – by parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts and other immediate relatives.

- The lifestyle of earning status: In most African traditions, there were rights of passage that signalled the movement of one’s status as one grew. A moran was not one, legend goes, until he had successfully fought a wild animal such as a lion. One did not become an elder until they had fulfilled certain criteria and until the elders had taught them how to be an elder. Everything was taught – how to handle wealth, people, land and so on.

- The work ethic: “He who has not worked must not eat,” was a mantra that rang true in many societies of past centuries from the jews and the arabs, to the people’s of the far east to our people in Africa. Work was encouraged and it needed to be quality work. A person’s pride came from the quality of the work that they did, whether they had acclaim or not. Today, we are starved for praise such that we all want to be stars and no one finds pride in sweeping a floor or unclogging a toilet or serving others.

A true measure of success for the future will be, in my view, just how grounded our people will be even as we develop our world into a veritable Wakanda.