Let’s explore the Passbook era in Kenya, a chapter in the nation’s history that is both poignant and often underrepresented. This period, spanning from 1947 to 1978, sits between the deeply resented Kipande system and the emergence of more modern forms of identification. It’s a story of control, discrimination, and ultimately, the slow march towards equality and justice.

From Kipande to Passbook: A Shift in the Mechanics of Oppression

To understand the Passbook, we must first revisit the Kipande. Introduced in 1919, the Kipande was a metal container worn around the neck by African men, akin to a dog tag. This wasn’t merely a form of identification; it was a tool of subjugation. The Kipande was issued under the Native Registration Ordinance of 1915, and it contained an individual’s fingerprints, employment history, and even a record of their movements. It was designed to keep African men under the watchful eye of the colonial administration, ensuring they remained where they were most useful—toiling away in the service of European settlers.

As David Anderson notes in his compelling book Histories of the Hanged, the Kipande was “a portable prison, a symbol of the deep indignity and oppression inflicted on African men by the colonial government.” It was hated and feared, a constant reminder of the low status accorded to Africans in their own land.

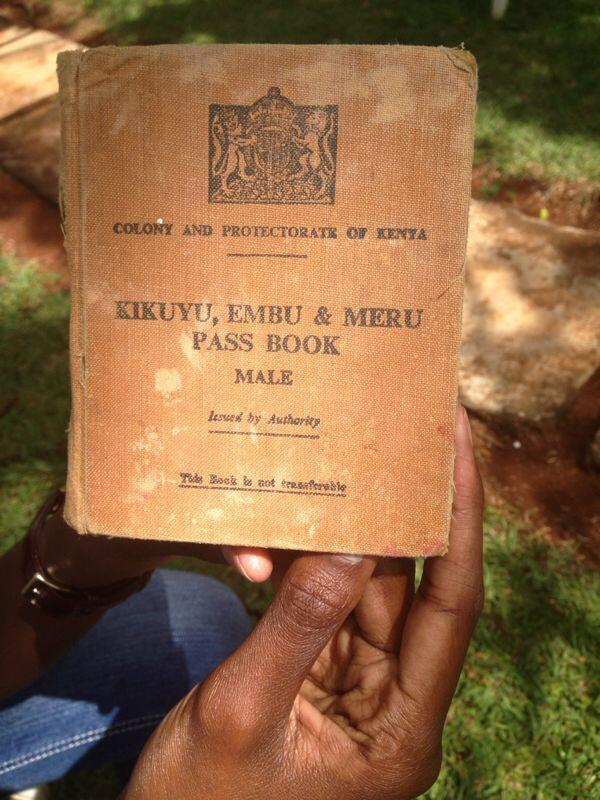

By the late 1940s, the winds of change were beginning to blow across Africa. Nationalist movements were gaining momentum, and the colonial powers were feeling the pressure. In 1947, the British colonial government replaced the Kipande with the Passbook, introduced under the Registration of Persons Ordinance. This new system was meant to be less overtly oppressive—at least on the surface. The Passbook was a booklet that contained an individual’s fingerprints but notably excluded photographs, meaning that identification was still heavily reliant on subjective physical markers.

A Tool for Maintaining the Colonial Order

The Passbook may have appeared more civilised than the Kipande, but its purpose was much the same. It was primarily issued to African men and was designed to regulate and control the African population. The colonial authorities used the Passbook to monitor African movements, enforce labour laws, and maintain the racial hierarchy that placed Europeans at the top.

For the colonial administration, this document was essential. It was more than just a form of identification; it was a means of ensuring that the African populace could be controlled and contained. Historian Bethwell Ogot, in his seminal work A History of Kenya, describes the Passbook as “a quiet weapon of the colonial government, used to sustain the illusion of civility while perpetuating the reality of racial dominance.”

Africans were required to carry their Passbooks at all times, and failure to produce it on demand could result in harassment, fines, or even imprisonment. This constant surveillance and the accompanying threat of punishment reinforced the notion that Africans were second-class citizens in their own country. Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai captures the essence of this dehumanisation in her autobiography Unbowed, where she writes, “The Passbook was a daily reminder that we were always under suspicion, always needing to justify our presence in the land of our ancestors.”

HISTORY OF IDENTITY

Go through the history of our search for an identity system over the years.

- The Kipande (1919-1947): A Symbol of Colonial Control and Oppression in Kenya

- The National Identity Card (1978 to date)

The Maisha Ecosystem

Gender Discrimination: A Deliberate Exclusion

One of the most glaring injustices of the Passbook system was its gender bias. The Passbook was designed almost exclusively for men, reflecting the patriarchal values of both the colonial rulers and the societies they governed. Women were largely excluded from the registration process, which meant that their legal rights, movements, and identities were not formally recognised. This exclusion was a deliberate policy aimed at keeping women in a subordinate position, both socially and economically.

Women’s exclusion from the formal identification system had significant implications. Without a Passbook, women found it harder to assert their rights, access services, or move freely. This exclusion perpetuated the patriarchal control over women, as they were often required to rely on male relatives for legal and economic transactions.

It wasn’t until 1978 that this gender discrimination began to be addressed. The Registration of Persons Act was amended to include women, marking a significant shift in Kenyan society. This amendment was the result of years of advocacy by women’s rights groups, as well as a growing recognition of the vital roles women played in the economy and society. This was a landmark moment in the fight for gender equality in Kenya, representing a broader move towards inclusivity in civil registration.

The End of the Passbook Era and Its Lingering Legacy

The Passbook era officially ended in 1978, but its legacy is still felt today. The transition to a more modern identification system reflected broader changes in Kenyan society. As the country moved towards greater equality, it sought to shed the remnants of its colonial past. The inclusion of women in the registration process was a crucial part of this transition, recognising their full citizenship and legal rights for the first time.

Yet, the scars left by the Passbook system are deep. For those who lived through it, the Passbook is remembered not just as a piece of paper, but as a symbol of oppression, control, and the relentless intrusion of the colonial government into their daily lives. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o famously said, “It was a small book, but it carried the weight of a thousand injustices.”

For further reading on this topic, I recommend visiting the Kenya National Archives, where original documents from the colonial period are preserved. Additionally, John Lonsdale’s works, particularly Mau Mau and Nationhood, offer a detailed analysis of the period, including the socio-political dynamics that shaped the use of identity documents in colonial Kenya. These sources will provide a richer understanding of how the Passbook and the systems that preceded and followed it shaped the Kenyan experience under colonial rule.