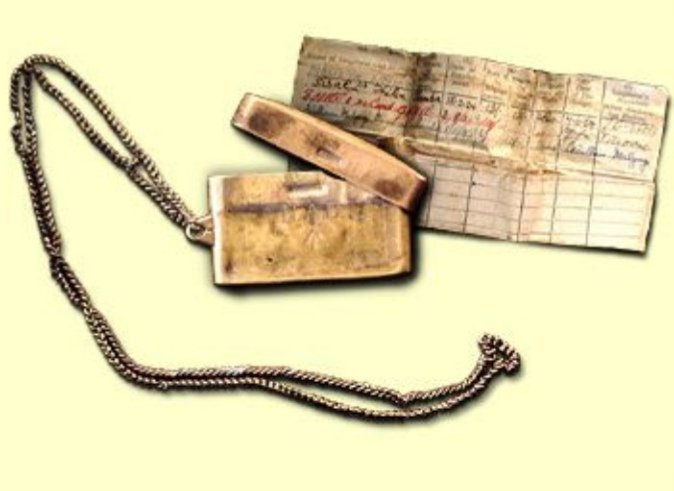

The kipande identity system, introduced by the British colonial government in Kenya in 1919 under the Registration of Native Ordinance No.15 of 1915, was far more than just an identification document. It was a tool of control and surveillance, deeply ingrained in the colonial agenda to dominate and monitor the lives of Kenyan Africans. This small metal container, typically worn around the neck, held a piece of paper detailing the wearer’s fingerprints, employment history, and physical description. But its significance went far beyond these details—it was a daily reminder of the relentless grip the colonial authorities had over African lives.

How the Kipande System Worked

Imagine being an African male over the age of 15, required by law to carry this metal box at all times, a constant reminder of the chains binding you to the colonial system. The kipande was used to track and restrict your movement, especially if you worked in urban areas or on settler farms. Every kipande was stamped with your name, age, ethnicity, and employer details, effectively tying you to a specific job and location. Your freedom to seek better opportunities or move elsewhere was not yours—it was dictated by the colonial authorities.

If you came from rural Nyanza or Kikuyu lands and sought work in Nairobi or the White Highlands, you had no choice but to register with the colonial government to get a kipande. Without it, you could be arrested for vagrancy. This small metal box was not just an ID; it was also a work permit. Every job you held was recorded in your kipande, and your employer was responsible for updating it. This system gave employers immense power over their workers, trapping them in jobs with no easy way out. A dispute with your employer could mean your kipande wouldn’t be updated, leaving you stuck and powerless.

HISTORY OF IDENTITY

Go through the history of our search for an identity system over the years.

Life Under the Kipande System

Life under the kipande was more than a bureaucratic hassle—it was a dehumanising experience. Wearing it around your neck was not just uncomfortable; it was a public symbol of your subjugation, a constant reminder of the colonial authority looming over you. Failure to produce your kipande on demand could result in severe punishment—fines, imprisonment, or even physical abuse. The psychological toll was immense. The fear of punishment and the weight of constant surveillance left many African men living in a state of perpetual anxiety.

The kipande was designed to enforce the colonial government’s economic policies, ensuring a steady supply of cheap labour for European settlers, particularly in agriculture and public works. It was a badge of control, stripping away the dignity of those forced to wear it.

Voices Against the Kipande

But the oppressive nature of the kipande didn’t go unchallenged. It became a focal point of resistance, symbolising everything that was wrong with colonial rule. Many African leaders, like Harry Thuku, stood up against it, speaking out against the way it stripped Africans of their dignity and freedom. Thuku, a pioneering political leader, founded the East Africa Association in 1921 and became a vocal critic of the kipande system, seeing it for what it truly was—a tool of exploitation and oppression.

Thuku’s activism wasn’t just talk; he organised strikes and protests, leading to his arrest in 1922. His arrest sparked the Thuku Riots in Nairobi, where thousands of Africans gathered to demand his release. The colonial police brutally suppressed the riots, resulting in the deaths of several protesters. Thuku’s resistance highlighted the deep-seated anger and resentment that the kipande system had generated among Kenyans.

It wasn’t just the leaders who resisted. Ordinary Kenyans found ways to defy the system. Some avoided registering for a kipande altogether, risking arrest. Others, forced to comply with the law, would sabotage the system—by not wearing the kipande or tampering with the information inside. The kipande became more than just a piece of metal; it became a symbol of the broader struggle against colonial exploitation, fueling the growing nationalist movement.

Colonial Justifications and the Reality

The colonial government justified the kipande system as a necessary measure to regulate labour and prevent crime. They claimed it kept track of the African population in urban areas, ensuring that only those with legitimate employment could remain. But this narrative was a thin veil over the reality: the kipande was a tool to suppress African economic mobility, maintaining a cheap and easily controlled labour force for European settlers.

The system entrenched economic and social inequalities, limiting Africans’ opportunities to move freely or seek better livelihoods. Many were forced into low-paying, unskilled jobs, with little hope of improving their economic status, all because of the restrictions imposed by the kipande.

End of the Kipande System

The kipande system continued to stir tension and conflict until it was finally abolished in 1947, as the colonial government attempted to placate growing African unrest and demands for greater rights. But by then, the damage was done. The system had left an indelible mark on Kenya’s social and political landscape, contributing to the radicalisation of the nationalist movement that would eventually lead to independence in 1963.

The legacy of the kipande lingers in Kenya’s contemporary discussions around identity and surveillance. The memory of this oppressive system has made many Kenyans deeply wary of government attempts to centralise and control personal data, as seen in debates around the Maisha Namba and other modern identity systems. The kipande is a stark reminder of how identity systems can be wielded as tools of power and control, and it serves as a cautionary tale as Kenya navigates the complexities of modern governance.