The First Generation ID: A New Beginning

In 1980, Kenya introduced the First Generation National ID Card, a significant step forward for a nation still finding its footing after gaining independence in 1963. It followed the KIpande (1919-1947) and the Passbook (1947-1978). This ID card was a laminated piece of paper that carried the essential details of every Kenyan citizen over 18—name, date of birth, gender, residence, a photograph, a thumbprint, and a signature. For many, this ID wasn’t just a document; it was a symbol of belonging to a newly independent Kenya, a ticket to participate fully in civic life.

However, while the introduction of the First Generation ID was a move towards modernisation and inclusion, the reality on the ground was often far more complicated. Obtaining an ID was no simple task. The process could be slow, bureaucratic, and frustrating, especially in rural areas where government services were sparse. People would travel for miles, wait in long queues, and sometimes face delays that stretched on for months. Corruption didn’t help matters either; there were always whispers—and sometimes outright demands—for bribes to speed up the process.

For young Kenyans in the 1980s and 90s, having an ID was crucial—not just for accessing services but also for staying out of trouble. Police patrols were common, and officers often stopped people to check their IDs. If you didn’t have yours on you, you were in for a tough time. James, a young man from Nairobi, still remembers the fear he felt one night in the late 1980s when a police patrol stopped him. He had forgotten his ID at home. The police didn’t care; they made him and a few others walk with them throughout the night, patrolling the city. It was a gruelling experience that left him exhausted and terrified, but it was also a stark reminder of how important that little card had become in daily life.

HISTORY OF IDENTITY

Go through the history of our search for an identity system over the years.

- The Kipande (1919-1947): A Symbol of Colonial Control and Oppression in Kenya

- Kenya’s Identity History: The Passbook (1947-1978)

The Maisha Ecosystem

The Second Generation ID: Modernisation with Old Challenges

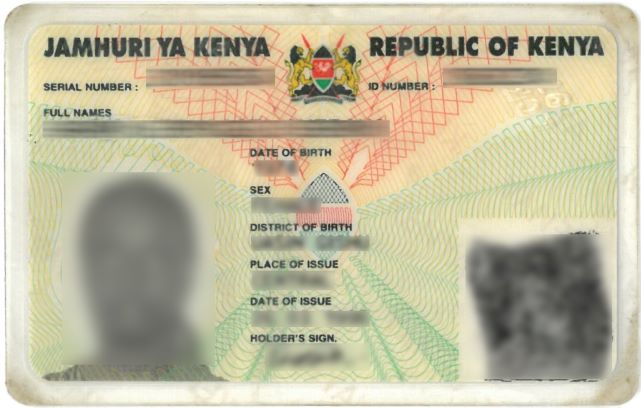

By the mid-1990s, it was clear that the First Generation ID, though revolutionary for its time, was beginning to show its age. Kenya was changing rapidly, and the demands on its identification system were growing. The government needed something more secure, more durable—something that could stand up to the rigours of a modern, increasingly digital society. And so, in 1995, the Second Generation ID Card was introduced.

This new ID card was a significant upgrade. It was credit card-sized, made of durable plastic, and featured enhanced security elements like holograms and watermarks. It was designed to be more resistant to wear and tear, and much harder to forge or alter. This new ID was a welcome change for many Kenyans—a modern, sleek card that felt like a step into the future.

But while the Second Generation ID was a technological leap forward, it didn’t solve all the problems of the past. The process of obtaining the new ID was still fraught with delays and bureaucratic hurdles. In some areas, particularly in rural Kenya, people faced long waits, sometimes stretching into years. The vetting process, especially for certain communities, remained a significant hurdle.

The Struggles of Marginalised Communities

For Somali, Nubians, and Makonde communities, getting an ID was more than just a bureaucratic task—it was a battle for recognition. These communities often had to undergo extensive vetting processes, where they were required to provide additional documentation and even bring in elders to testify to their Kenyan citizenship. This process was not only time-consuming but also deeply humiliating, as it questioned their very identity and belonging in the country.

Amina, a young woman from the Somali community in Garissa, remembers the challenges she faced to get her Second Generation ID in the late 1990s. “It felt like we were being put on trial, just for trying to prove that we were Kenyan,” she recalls. The vetting process meant bringing in her parents and sometimes even her grandparents to testify that they were Kenyan citizens. It was a frustrating and painful experience, made worse by the feeling that they were being treated as outsiders in their own country.

The challenges were even more pronounced for stateless people, like the Makonde. Originally brought to Kenya from Mozambique as labourers by the British in the 1930s, the Makonde lived without recognition or IDs for decades. It wasn’t until 2016, after years of activism and a historic march from Kwale to Nairobi, that the Kenyan government finally recognised them as citizens and issued them IDs. This victory was a long time coming, but it also highlighted the deep-seated challenges many stateless people face in their quest for recognition.

Reflecting on the Journey

The evolution of Kenya’s National ID system from the First Generation in 1980 to the Second Generation in 1995 and beyond reflects the broader journey of the nation itself. These ID cards were more than just documents; they were symbols of citizenship, belonging, and progress. However, they also revealed the persistent inequalities and challenges many Kenyans faced, particularly those from marginalised communities.