A few days ago, I had the opportunity to hang out with Arizona State Representative, Stephanie Mach, in a session where she talked about herself and her life’s work as a State Rep for District 10. She took time off her re-election campaigns to come and talk to Washington Fellows at the Arizona State University. She is an amazing woman – confident, passionate and clearly very driven – certainly more than a lot of politicians I have met (and I have met many).

What struck me second, was how little of an entourage she had around her – she had none. In Kenya, she is the equivalent of a County Representative and they already have bodyguards and PAs. She told us that she is paid $24,000 a year and that when they have special functions or meetings she is paid $60 per day for a maximum of a couple of days – not more than a week.

What struck me first, you ask?

Well, Stephanie looks rather different from what other people look like. “You may have noticed that I look somewhat different from you and others,” she quipped about midway into her talk. The story behind that is that when she was 17, she was involved in a car accident (in Kenya we always add an adjective to car accident, e.g. grizzly) in which she sustained burns on 65% of her body and at which she lost her right arm. She was legally blind (see here for definition) for a couple years after that.

She amused us when she told us about how as a self-conscious teen she tried to pretend that she could see, walking about school. “it was hilarious,” she laughed.

How Stephanie handles her body was a particularly special and illuminating thing for me and it clarified a great deal for me. First, she didn’t at all carry herself as I have seen a lot of people with disabilities do. She has championed the cause of that constituency in the House where she lodged a bill for people with disabilities. But she didn’t wear it on her sleeve.

I was very pointed in my questions to her.

“What are your views regarding affirmative action?”

She supports affirmative action – but the examples she gave of situations that demand affirmative action did not go down the standard lane you would expect a person with disability (that is such an unwieldy phrase) to give. She talked about young people and their access to internship as an example. “Most internships in the US are not paid,” she explained. So often the people who are able to take internships are people from better off families who have transport and food money and such. People who have to work through out are marginalised because we don’t recognise working at starbucks as relevant experience in an accounting firm for example. “We need affirmative action for that young person from a poorer background to access the internships.”

After we had talked about immigration, poverty in Arizona, the environment and so on, I decided to ask about her. I pointed out that she was disabled and she didn’t express herself from that experience. “Why?” I wanted to know. And at this point she blew my mind.

“You know, ability is measured by the task. If you wanted me to lift a much of tables and move them to the other side of the room, then yes, I am disabled (not having one hand). But if you wanted me to work on a computer, then I am not disabled because I can. I don’t see myself as a disabled person and even when I am campaigning I don’t campaign on that platform, I talk about the things people care about – immigration, incomes. My disability comes up conversationally, for example when we are talking about healthcare and I can show them that I empathise with their need for better healthcare because I have needed it in the past. I am a representative for all citizens of my District, not just the disabled.”

“ABILITY IS MEASURED BY TASK” – Stephanie Mach, State Rep, District 10, Arizona.

And then she said, “How you view yourself, dictates how other people view you.”

Since that talk by Stephanie Mach, I have been reflecting about how disabled people are supported in the continent. Of course I have to think of it in the lense of my marketing background. I am aware of many organisations in Africa that work towards the better inclusion of the disabled in our societies. But I wonder about how they are positioned in the minds of governments and corporations and donors.

Forgive me, but I am about to wade into politically INcorrect ground here. There is not enough engagement by non-disabled Africans like myself because we are afraid to be politically incorrect or to sound insensitive. But how else can we become a part of the issue if we don’t engage honestly? We can’t learn from each other unless we do. Also, disclaimer: I will be rather generalistic for purposes of this conversation.

One of the Washington Fellows at the Arizona State University is Lois Auta, a Nigerian woman who was affected by Polio when she was two. What’s interesting about Lois is her passion for the cause of people living with disability. She is a leader in her country in the space of advocacy for the issue and she runs a foundation that she founded, Cedar Tree Foundation. After the talk by Stephanie, we have been reflecting on the issue and she has led me to better understand the African dilemma for inclusion of disabled people.

Facts:

- the disabled are the least served group of people in Africa

- there are over 60 million Africans living with disability

- few (if any) countries have laws that support the inclusion of people with disabilities

- out of Africa’s population of the poor, disabled people are a significant percentage and the statistics go on to illiteracy, under education and so on.

Majority of disabled people that I have listened to like my friend, Lois have told us, able bodied people again and again about the plight of the disabled to the point that we can tell the story ourselves (often as we pat ourselves in the back for having made some token contribution to some charitable initiative for the disabled).

What I realised as I listened to Stephanie Mach, is that there may be an opportunity to advance the cause of disabled people further but it will involve, in my humble opinion, some significant radical thinking on the parts of everyone – especially the leaders who advocate the cause.

“persons with disabilities can be assisted with mobility aids because many of us are crawling on the ground due to lack of wheelchairs, crutches etc”

I saw this phrase in an actual proposal for support of an initiative for people with disabled people and it underscores the point I am struggling to make. That despite the facts above and more being true, we have to start selling the ABILITY not DISABILITY of people with disability. We have to talk less about how disadvantaged they are and talk more about the potential that they have – what they have to offer society (which I believe is a lot). In the case of that phrase above, I wonder, where is this person crawling to? To work (whatever his job)? To school? To some gainful activity that makes the world a better place?

My view is that disabled people are people first. They have the same societal aspirations that everyone else has – good life, family, a good home, good cities and safe neighbourhoods, good meals and great friends. Disabled children have the same potential as able bodied children – they can be wealthy, they can be political leaders, they can be accountants, engineers lawyers etc. They can overcome their poor backgrounds and claw their way into the middle class as able bodied kids from poor families do. The potential is the same. Except that they need just a little more support to get around and to do what they need to get done.

I think there is an opportunity for leaders in Africa – especially leaders advocating for the rights of the disabled to start selling the potential of the disabled as tax payers, as great employees and productive citizens. We need to show that by ensuring that a physically challenged person has a wheel chair or crutches then they are enabled to be productive citizens of our societies. I say show not say. There needs to be more research that demonstrates that they work hard like the rest of us to make life better for themselves and for us. We need to show that disabled people can campaign for elective offices and represent the needs of all citizens (because the voters will be all citizens). We need to show that they can excel in business and make money.

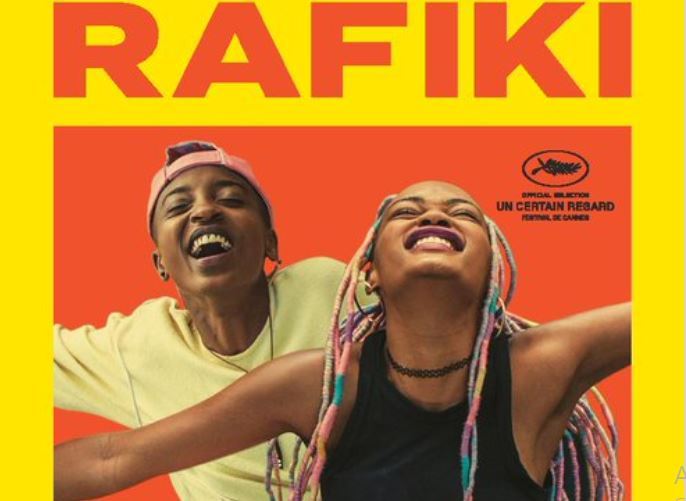

Speaking as a marketing professional, I am arguing that we need to reposition the cause in the minds of the people who have the influence to make the necessary changes. To do so we need to update our arguments. To say that they need to be supported is not enough. When the argument ends there, it suggests that they are hopeless people who need charity instead of people who need some investment in them so that they can add value to society. I am arguing that it would be great to have “posterchildren” who demonstrate the value cause to those who have less knowledge than they need to have empathy. These poster children for me are a elected (not nominated) members of Parliaments, a wealthy businessman, a successful doctor. I look forward to seeing more magazine covers like his one.

In Nairobi at the City Market there are three disabled gentlemen that I know who have spent decades at the market begging from the customers. With the proceeds, they have educated their children, bought land and built very nice houses. To this day, they continue to beg at that market. I think some work has to be done by the leaders who advocate for the disabled like Lois, to have tough conversations with people like these to say, this does not help the larger cause. It positions the disabled as beggars and we must change that perception. Yes, many will be forced to beg to survive, but it can’t be a means to thrive.

The children have to have people to look up to that they can say, I know I can be president because so-and-so is a Minister. I know I can be wealthy because so-and-so is a business leader. We must expand their horizons so that they know that they can be geneticists, biochemists, programmers, designers, artists, musicians and more. The most effective way to do that is to show them and the world.

Sort of the same way that when girls see Stephanie Mach as a State Representative, they know that a woman can lead and they can look forward to that. Sort of like when black South African kids see effective black MPs, they know that they too can be president and they look forward to that. And when white South Africans see fair effective black leaders in power they realise, they had nothing to be afraid off all the years of apartheid.

Its time we started to market ability, not disability.

Al, something you said invokes our topic of “ethical engagement, and deserves a comment: “There is not enough engagement by non-disabled Africans like myself because we are afraid to be politically incorrect or to sound insensitive.”

Caring people want to discuss the ways in which society disadvantages or even oppresses people who are “different” than the majority. They know that discussion is necessary for change. But simultaneously they may be apprehensive about putting forward opinions about sensitive or highly politicized issues, fearing that their lack of personal experience or even their lack of “standing” as a member of the majority may unintentionally trigger someone’s discomfort or worse.

Those of us who are not disabled are afraid to offend the disabled. Many who are white are afraid to engage in discussion of issues that particularly beset people of color. Those who are not heterosexual, those without homes, those who are unattractive, those with mental illness, those who cannot read, those who are foreigners, those who have socially stigmatizing illnesses and so forth. Many of us are afraid to engage around these issues.

However, as you have pointed out, the courage to engage is necessary for change to occur.

Years ago, I participated in something called the Diversity Infusion Institute through the University of Missouri, where I was taught to be more aware of the diversity in my classrooms, and to make it safe and respectful for all students to be exactly who they are. During that experience, I learned both how easy it is to accidentally marginalize someone by talking when you come from a place of not knowing (why we’re all afraid). But I also learned that it can be just as easy to engage in these difficult conversations if you are willing to admit out loud to the limitations of your experience and knowledge, ask questions from a genuine place of curiosity (like you did with Representative Mach) and then be a listener – be open to what you hear and be aware that someone’s perceptions of their own circumstance is likely to be more authentic than whatever you imagine or your taught ideologies suggest.

The only way to get good at these conversations is to try them, over and over, until you are comfortable. For one of my classes, I lead a session on our diversity where I let everyone label themselves, talk about labels and demographics and personal characteristics, and how labels may in some ways disadvantages us and in other ways advantages us (can you think of a way in which the label “disabled” might advantage someone?). These conversations are had with respect so that people feel safe to talk from their own, authentic experiences, and as such can be some of the most educational and perspective-shifting ever. One year, I had a young woman come to me after class to say that this was the first time in her life she felt safe enough to talk out loud about the fact that she was overweight, and what that experience was like for her. She thanked me profusely for making that conversation possible for her.

Part of the lesson of Representative Mach is that her attitude is only half the equation. One of the most powerful ways to create social change is for the rest of us to recognize, accept and insist on dignity and a “whole humanness” orientation toward those who are disabled. When we come from that place, those conversations are genuine and much easier to have – and like the student in my class, I think there will be a lot of gratitude to you for making the conversation possible.