Last week, I attended a meeting presided over by Amb. Prof. Julius Bitok, the Principal Secretary of the State Department for Immigration & Citizen Services. It was a Public Participation exercise on the Maisha Namba, Kenya’s new Unified Personal Identifier meant to replace the National ID Card and all other numbers associated with a person living in Kenya.

The primary advantage of the Maisha Namba is its potential to simplify the identification process. By consolidating various identifiers into one, the UPI promises to make interactions with government and private sector services more seamless. It is expected to enhance service delivery efficiency, reduce fraud instances, and ensure that individuals’ identities are easily verifiable across different platforms.

Furthermore, the Maisha Namba could be crucial in fostering financial inclusion by providing a single, reliable identifier for accessing banking and financial services. Maisha Namba could transform healthcare in Kenya by tying all your medical records to a single ID. Imagine going to any clinic or hospital; the doctor instantly knows your full medical history, no matter where you’ve been treated. This would mean better care, fewer mistakes, and faster treatments. Plus, it could help the government keep track of health trends and ensure resources go where they are needed most, making the whole system work better for everyone.

Maisha Namba could also simplify everyday tasks by streamlining how we access services. Instead of juggling multiple IDs and numbers for banking, government services, or even getting a SIM card, you’d only need your Maisha Namba. It’s like having a single key that unlocks everything, making life more convenient and reducing the hassle of paperwork. Plus, everything connected to one ID could help reduce fraud and make transactions more secure, giving people peace of mind when handling personal information.

Too many identifiers today

In Kenya, from the time you are born to the time you die, you need many unique identifiers to get services. These include:

- Birth Certificate Number

- National Education Management Information System (NEMIS) Number

- National ID (Kitambulisho) Number

- Voter Registration Number

- Driving License Number

- Passport Number

- Mobile phone number (for money transactions)

- Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) PIN

- Marriage certificate number

- National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) Number to be replaced with Social Health Insurance Fund (ShIF) Number

- National Social Security Fund (NSSF) Number

- Death Certificate Number

I have not included private sector services in this list, which also provide their numbers.

HISTORY OF IDENTITY

Go through the history of our search for an identity system over the years.

- The Kipande (1919-1947): A Symbol of Colonial Control and Oppression in Kenya

- Kenya’s Identity History: The Passbook (1947-1978)

- The National Identity Card (1978 to date)

The Maisha Ecosystem

The Maisha Namba is at the heart of the Maisha Ecosystem, a unique identifier assigned to every Kenyan citizen from birth. This number is set to replace the existing identifiers, such as the National ID number, KRA PIN, and NHIF number. The Maisha Number will serve as the single, lifelong identifier for all Kenyans, intended to simplify access to government services and improve administrative efficiency.

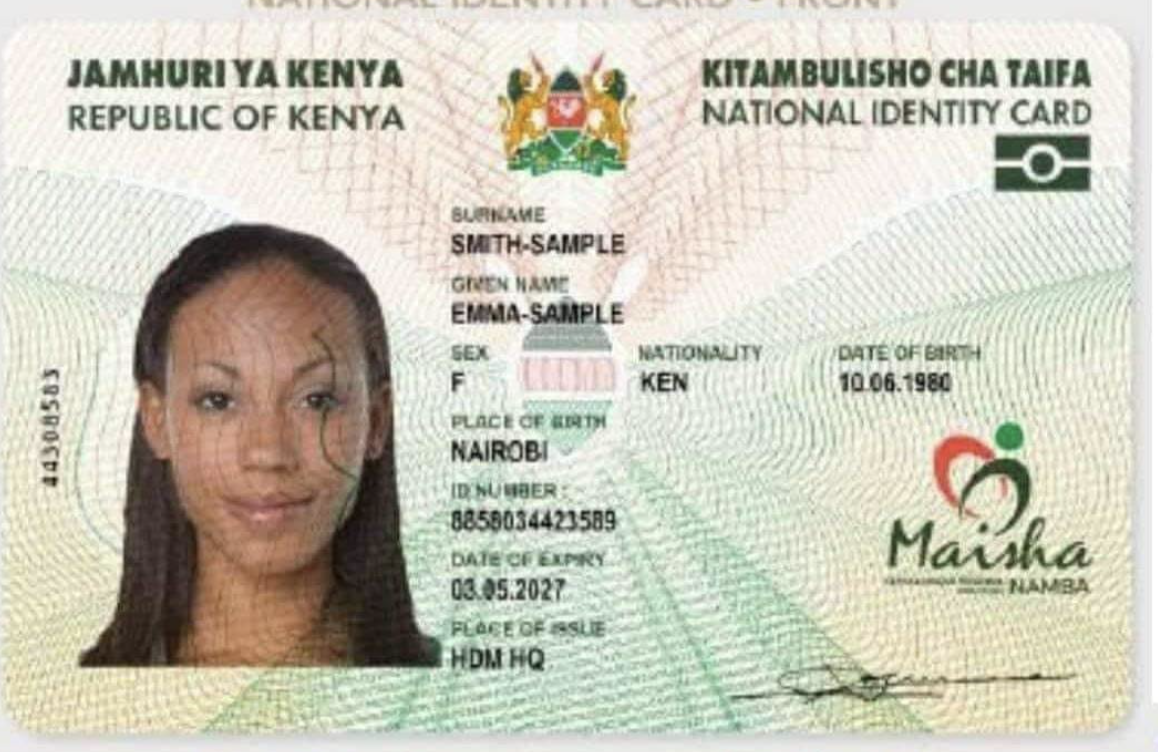

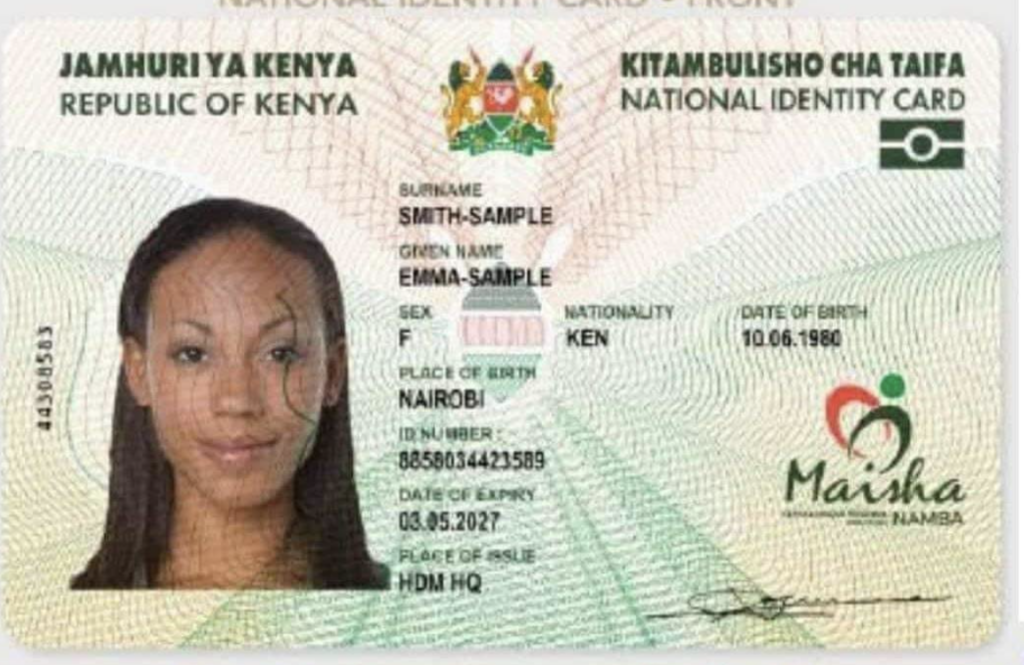

Accompanying the Maisha Number is the Maisha Card—a physical card embedded with a chip that stores personal data. This card will not only serve as proof of identity but will also be vital in accessing a wide range of online and offline services. From banking to healthcare, the Maisha Card is designed to be a one-stop solution for verifying identity and facilitating transactions.

All the data associated with the Maisha Namba and Maisha Card will be stored in a centralised Maisha Database. This database, which used to be the Integrated Population Registration Database System (IPRS), is expected to consolidate existing independent databases, creating a unified system that is easier to manage and more secure. The database will include personal information such as biometrics, which raises significant concerns about data privacy and security. The government plans to implement strict data protection measures to safeguard this sensitive information.

A crucial element of the Maisha Ecosystem is its integration with the eCitizen platform. eCitizen is Kenya’s official online portal for government services, and by linking the Maisha Namba to this platform, the government aims to streamline access to various services. Whether renewing your driver’s licence, paying taxes, or applying for a passport, the Maisha Namba will simplify these processes by acting as a universal identifier.

The Proposed Maisha Namba Rules: Modernisation is the intention

The first set of rules, the Births and Deaths Registration (Amendment) Rules, 2024, is about entering the digital age. The government wants to switch from old-fashioned paper-based records to a more efficient system that includes electronic records.

- Electronic and Loose-Leaf Registers: The rules introduce both loose-leaf and electronic registers to keep track of births and deaths in Kenya. This shift isn’t just about convenience; it’s about ensuring these crucial records are accurate and easily accessible when needed.

- Unique Personal Identification Numbers (UPINs): Every Kenyan will receive a Unique Personal Identification Number (UPIN) at birth, which will stay with them for life. This UPIN will also be linked to their death record, ensuring a seamless tracking system from birth to death.

- Updated Fees: The new rules update the fees for services related to birth and death registrations. For instance, getting a birth or death certificate will cost Ksh 200, while late registrations will incur higher fees. They’ve also introduced charges in US dollars for services like foreign registrations, signalling a more structured fee system.

- Changes in Birth Certificates: The birth certificate format will be tweaked to reflect changes, such as adopting a new surname after an adoption order. The idea here is to ensure that the birth certificate is always up-to-date and reflective of an individual’s current legal identity.

The second set of rules, the Registration of Persons (Amendment) Rules, 2024, focuses on revamping the national identity card system. The government plans to introduce electronic ID cards that are more secure and integrated with other personal data systems.

- Electronic and Digital ID Cards: Say goodbye to the old plastic IDs. The new rules allow electronic identity cards to be presented in digital or virtual form. This is a massive step towards making identity verification quicker and more reliable, whether at a government office or conducting online transactions.

- Biometric Data Collection: When you apply for your new ID, you will record your facial, thumb, and fingerprint biometric data electronically. This data is crucial for preventing fraud and ensuring that your identity is uniquely yours.

- Linking with Birth and Death Records: Your new ID will now incorporate the Unique Personal Identification Number (UPIN) assigned to you at birth. This ensures that your identity remains consistent throughout your life, from birth to death.

- New Application Forms: The rules also introduce new forms and schedules for applying for identity cards. These forms will require detailed personal information and biometric data, making the application process more thorough and secure.

- Revised Fees: There was some confusion about the costs during the meeting. The documents said one thing, and the presentations said something different, causing some confusion. According to PS Bitok, the cost of obtaining a new identity card is Ksh 300, and if you lose your card or need to change your details, it’ll cost Ksh 2,000. This fee structure reflects the additional costs of implementing these new technologies. It had been gazetted as Ksh1000, but he said it was revised to Ksh 300 in a subsequent Gazette notice.

What’s Good about Maisha Namba?

- Introduction of Unique Personal Identification Number (UPI):

- I have been a big proponent of this since the Kibaki days. The amendment mandates that all birth and death entries be assigned a unique personal identification number. This is a significant step towards improving the accuracy and traceability of vital records, ensuring that individuals’ records are consistently linked throughout their lives and even after death.

- Electronic Record-Keeping:

- The transition to maintaining birth and death registers in both loose-leaf and electronic forms is a commendable move towards digitization, which can enhance the efficiency, accessibility, and security of records. We can expect simpler processes like we have experienced with eCitizen.

- Streamlined Processes:

- The amendments aim to streamline processes by ensuring that changes such as adoption or re-adoption are promptly reflected in the birth certificates, making the document management process more seamless.

- Clear Fee Structure:

- The momentary confusion aside, the detailed specification of fees for various services related to births and deaths, including certification, late registration, and amendments, provides transparency and clarity for users of these services.

What are my Concerns on Maisha Namba?

- We are implementing as we design:

- We’re rolling out the Maisha Namba initiative while still ironing out the details, which goes against how such significant programs should be introduced. Typically, initiatives of this scale—especially those affecting millions—require meticulous planning, including pilot testing, risk assessment, and extensive consultations with stakeholders, from marginalized communities to data protection experts. Rushing into implementation without fully addressing these steps risks technical failures, potential data breaches, and the exclusion of vulnerable groups. Moreover, a premature rollout can spark public backlash if people feel left out or the system falters. Ideally, we’d take the time to perfect the design, ensuring that the final system is robust and secure and genuinely serves all Kenyans effectively and equitably.

- We are implementing for the most served instead of the least served.

- Instead of starting the Maisha Number rollout in well-served areas like Nairobi, we should design and launch it with the most underserved regions in mind. Counties like Tana River and Kilifi face significant barriers to accessing government services—distances to local chiefs are longer, transportation is sparse, and information dissemination is slower. Additionally, incomes in these areas are generally lower, making the costs and logistics of implementing the Maisha Number much more challenging. If we design the initiative to address these difficulties first, ensuring that people in remote areas can easily access and benefit from the system, the rollout in urban areas will naturally be smoother. Prioritizing these least-served regions from the start would ensure that the Maisha Number truly embodies inclusivity and equity rather than leaving the most vulnerable populations to struggle with a system that wasn’t designed with their needs in mind.

- The costs don’t make sense.

- The costs associated with the Maisha Number system just don’t make sense. Automation is supposed to make processes faster and more affordable, yet we’re seeing higher fees proposed for services like verification. How do we justify charging more when the system is becoming more efficient? Verification will be done via the eCitizen platform, and applications and processing should also be handled there. There’s simply no reason for applications, especially abroad or in remote areas, to physically travel to processing centres. It’s not just inconvenient—it’s unnecessary. This approach raises serious concerns that the Maisha system is being used as a revenue stream for the government, which is troubling because identity is the most fundamental of all rights. It should be accessible to everyone, regardless of income, without being used as a means to generate profit. The focus should be on making sure every Kenyan can easily and affordably obtain their Maisha Number, not on burdening them with avoidable costs that defeat the purpose of the system.

- Data Protection is a real concern.

- Significant data sharing and protection concerns surround the Maisha Number initiative, especially given the government’s plans to use extremely sensitive biometric data—such as facial, iris, and fingerprint information. The Principal Secretary, Julius Bitok and his team mentioned that four Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) have already been conducted. However, the fact that these assessments have not been made public raises serious questions about transparency and accountability.

- Making these DPIAs public would go a long way in building confidence among citizens and stakeholders. When you’re dealing with data as sensitive as biometric information, the data protection guardrails must not only be robust but also obviously apparent to the public. People must know exactly how their data will be protected and who can access it.

- One of the primary concerns is how data will be shared within the government. For example, how can we be sure that a KRA officer won’t have access to unrelated personal information, such as medical records, and misuse that data to conduct tax investigations? This cross-accessibility within government departments could lead to unsanctioned government surveillance, severely undermining public trust in the system.

- The government must clearly define how data will be shared across various agencies, ensuring that access is strictly limited to what is necessary for each department’s function. Moreover, stringent safeguards should be in place to protect citizens from any form of unsanctioned surveillance or data misuse. Without these measures, the risks associated with the Maisha Number could far outweigh its intended benefits, eroding the trust that this system is supposed to build.