See #IGF2022 reflections on Digital Reflections

Last week, I attended the Internet Governance Forum (IGF2022). By the end of it, I have had several reflections about what the opportunities there are for Africa. These are the conversations that I am really hoping to have and hear about on the continent in the coming year.

I share them here in point format so that we all consider them.

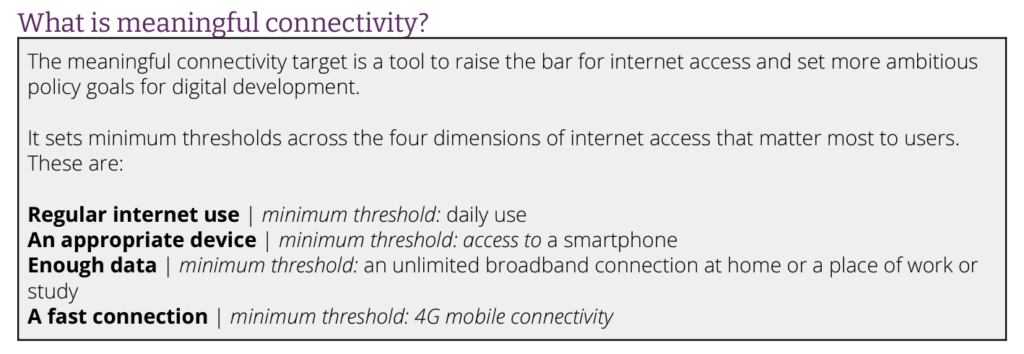

We must ensure Meaningful Internet Connectivity for all

There needs to be a multi-stakeholder engagement that discusses ensuring meaningful connectivity for all – especially those left behind in rural and remote areas. These discussions would centre around access and cost to (mobile) devices and a strong 4G network. They would focus on the internet’s cost and consider how people who earn USD 2 per day can pay for more access.

But while we think about that, we must create relevance to the internet for the millions of people left behind. For that to happen, there has to be relevant and relatable content to the millions of people in rural and remote areas. It is not enough to do educational audio and video on farming – a genre of content that is the most prevalent, done by well-meaning non-profits. There has to be “soft-sell” content that entertains and influences behaviour without “preaching”.

The best example I can think of is one of the ways that Hollywood contributed to the belief in much of the world that America is the greatest country in the world. Movie after movie after movie harped on the idea that America was the greatest country in the world – so much so that many people in the world were influenced to accept it as a fait accompli. My own socialisation is that I will watch Hollywood movies before I would watch movies from other places (followed closely by Nollywood movies – the rural kind not the upmarket kind) because I grew up on Mel Gibson, Jean Claue Van-Damme, Sandra Bullock, Laurence Fishburne and Denzel. I love me a good dysfunctional cop action drama.

Yet, in many measures, best articulated by the Newsroom TV drama star Jeff Daniels (I have inserted updated stats by me in italics). “There is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we’re the greatest country in the world. We’re 7th in literacy (35th in 2022), 27th in math (3rd in 2022), 22nd in science (1st in 2022), 49th in life expectancy (46th in life expectancy), 178th in infant mortality (146th in 2022), 3rd in median household income (5th in 2022), number 4 in labor force (number 3 in 2021) and number 4 in exports (2nd in 2022)…”

In similar ways, content has the power to influence people’s actions and beliefs in ways that improve their lives and outlook. By making sure that rural and remote populations have access to content that they find relevant and entertaining, there is a chance to promote new and better ways of life and also ensure that they also contribute content.

We need the internet to speak our language

At the IGF2022 it occurred to me that the next frontier for the internet to be an equaliser for everyone in the world is where the internet speaks everyone’s language. Imagine that this blog post could be read by internet policy enthusiasts everywhere in the world – in their own languages, without having to translate the blog post. Imagine that our browsers have the capacity to translate all websites to even the languages of the smallest tribes.

Imagine reading content written in the Min dialect of china could be read automatically in the Digo language in rural Kwale? Imagine a young lady in Addis Ababa reading an email or chat in Amharic from a penpal in Chincheros in Peru, written in Quechua? Imagine biologists in Ahmedabad, who only spoke Gujarati debating with Scientists in Senegal who were most comfortable with Wolof? I imagine chatting on Facebook with a Nepalese person – me writing in Kiswahili and them writing in Nepali. Imagine that the Facebook Engine translated automatically the conversation so that we each understood each other comfortably?

How do we get this done?

We – especially those of us in the global south – need initiatives that develop lexicons, dictionaries, and syntaxes in our languages. A lexicon is a collection of words and phrases used in a particular language, while syntax refers to the rules governing the structure and arrangement of words in sentences.

Developing a lexicon and syntax for a language involves a number of different steps and processes, including the following:

- Gather a large dataset of text in the target language: To develop a comprehensive lexicon and syntax for a language, it is essential to have a large and diverse dataset of text written in that language. This dataset should include a wide range of different texts, including news articles, books, and other written materials, to provide a comprehensive picture of the language.

This is something that needs governments and civil society organisations to drive awareness and invest in knowledge creation, content publishing by citizens – having citizens write books and publish stories in the local vernacular. - Use natural language processing techniques to analyse the dataset: Once a large dataset of text in the target language has been gathered, the next step is to use natural language processing (NLP) techniques to analyse this text and extract key features and patterns. This process involves using algorithms to identify and extract important language features, such as grammar, syntax, and vocabulary, to build a comprehensive language model.

We need to grow our Tech-Diplomacy

Perhaps the most important session that I attended was one organised by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change entitled Growing a New Cadre of Tech Diplomats. As Africans and people in the general global south work to strengthen their position, including in the ways I suggest above, an important building block will support that work is tech diplomacy. I wasn’t quite very aware of the concept of tech diplomacy until I listened to the panelists, especially Sinit Zeru (left), the Ethiopia Digital Transformation Strategy Implementation Lead and a senior advisor at the Tony Blair Institute.

What is Tech Diplomacy?

I understand there are a couple of ways to look at tech diplomacy. First, it is the use of ICT and the internet in the conduct of diplomacy. The more relevant explanation of the concept is that many big tech companies now have amassed more power than many countries. Some countries have appointed actual ambassadors to the big tech community in Silicon Valley. Denmark was the first such country but several others have followed suit.

“With the rise of the influence of technology, governments realised they needed to have someone on the ground liaising directly with these behemoths of non-state power,” Patricia Gruver, tech policy manager at the nonprofit Meridian International Center is reported to have said in this DEVEX article.

At the IGF2022 session, I learnt that there is an opportunity for African countries to develop stronger policies that may attract investment by big tech in their countries, as I heard Daouda Lo, the Head of Tech for TBI in Senegal, say. But even as they do that, it is important to consider the power dynamics that come into play in these relationships and managing those dynamics require that we grow skills in tech diplomacy – not just in government but also within CSOs that have some sway to influence government and also big tech.

Indeed, it was an exciting thing to discover a new career.

The time for Africa’s GDPR is now.

In 2014, the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection, popularly known as the Malabo convention, was passed. It is meant to establish a ‘credible framework for cybersecurity in Africa through the organisation of electronic transactions, protection of personal data, promotion of cyber security, e-governance and combating cybercrime…’

This very progressive document has not come into force eight years down the line, as only 13 out of the 54 African states have signed and ratified the convention. The document requires 15 states to ratify the convention for it to be enforceable – or at least for it to be considered for legal purposes.

The question of data governance is something that has been at the forefront of our mind as my colleague Tom Orrell, CEO Data Ready and I worked hard to get Africans to proclaim a set of principles that would encourage African states to establish policy, legislation and/or structure that ensures data protection and privacy rights – especially in the Covid-19 era. Through the Restore Data Rights initiative, a group of organisations pushed for the signing and adoption of the declaration that was formed.

It was not very successful as getting many people to sign it was harder, although they thought it was a good thing.

Now in partnership with Amnesty International Kenya, we have resolved to engage with the East African States to encourage them to establish an East African framework and law for data protection that would regulate governments and tech and data companies.

Youth must step up into the conversation

I enjoyed a small session organised by Catherine Kirambo, the Executive Director of African Child Projects (Tanzania), Lily Edinam Botsyoe of Hacklab Foundation (Ghana) and Gabriel Karsan, founder of the Emerging Youth Initiative (Tanzania). The three young leaders facilitated a conversation about how to get young people into policy conversations especially around issues of internet and ICT governance.

My thoughts and takeaways were that we must acknowledge that youth are not a homogenous lot. Unfortunately, they suffer many generalisations – either they are unaware and unexposed to policy or, like in the case of many of the youth at the conference, were switched on and talented and keyed in. I opined that it should be placed on those who have not only the youth networks to listen to their voices and then translate them into policy speak. However, I feel strongly that policy wonks need to turn around and invite young people onto decision-making tables.