2021 is promising to be a year of some fundamental changes for me. It started with our organisation implementing a decision for our team to permanently work from home, as a means for us to stay safe, but also for our programming to start to spread across the African continent even more. The year also started with me choosing to start moving away from the capital city, Nairobi and move to Malindi, my hometown by the beach. There, I have developed a bug for farming and I am looking at producing Cassava, Pineapples and honey.

Let’s go back a bit. On January 6th 2000, I moved to Nairobi from Malindi, having defied my parents decision to send me to Italy to live and work. I was convinced then that my future is in the capital because it was there that I could make a difference to Kenya, my chosen home. Look at it this way: in 2000, Kenyans were at the height of their dejection of Kenya’s prospects. President Daniel arap Moi had already occupied his presidential throne for 22 years and the economy was in a horrible state. Corruption in Kenya was so legendary that you could not home for the most basic of services without “Kitu Kidogo” (something small). Even walking on the street was perilous – if not from the petty thieves who would snatch bags and even earrings from unsuspecting ears, then from the police who would stop and frisk you for any pennies you have.

Nairobi was so notorious that it had the Moniker, ‘Nairobbery’

“Early 2000’s Nairobi, had a sense of urban culture maturity about it. The exponential cultural growth of the 90’s had morphed into a plateau. If urban growth lexicon has a term like a “nascent metropolis”, that would be 2000’s Nairobi in two words.”

What is Nairobbery?

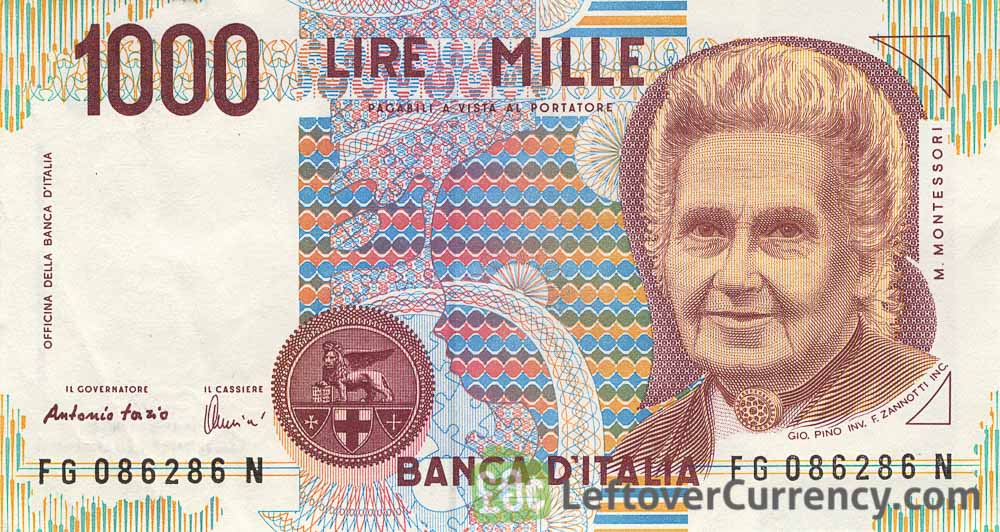

I experienced this myself first hand in Nairobi several times over the next couple of years. One day, I was walking down river road, heading to the bus terminal to take a bus home to Malindi in the evening. Two policemen stopped me and asked me to produce my ID card while at the same time asking where I was going, where I was coming from and so on. “Umebeba nini,” one asked as he rummaged through my pockets. What am I carrying? He found my wallet and in it was a single note of 1000 Italian Lire (Italy’s money before the Euro). At the time, 1000 Lire was not even worth buying candy in Kenya. Maybe Kshs 10 at the most.

Hii utawachia sisi, uende. You will leave us this and we’ll let you go. I have never negotiated more desperately for money like that. I convinced them that 1000 Lire was a lot of money and I needed it most urgently. I had nothing else on me, I told them and this is all I have between me and destitution. They can’t take all of it.

Eventually, they felt pity on me and roughly gave me Kshs. 500 and told me to be on my way or they would shoot me. I left. In the bus, I had mixed emotions. Frustration at being so blatantly stopped and frisked for no reason and at the corruption of it all. I also felt massive glee for having outsmarted the cops. I laughed heartily at imagining that cops face, when the next day he discovers that he gave me 500 bob in exchange for 10 bob!

I chose to stay in Kenya when everyone else was living because, you buy stock when they are down. I bought Kenya’s stock when it was at its lowest – GDP at negative growth, public optimism at its most hopeless. It turned out to be a good decision looking at my carrier so far. Over the past 20 years, I saw the economy soar and became part of the team that added value to establishing infrastructure for its continued growth – especially in the realm of technology.

Instead of waiting on tables in Bologna, Italy, I was contributing to establishing fibre connectivity in Kenya. My mother, who 20 years ago was convinced that I was an incautious throwing my life away, eventually became proud of the man I became.

Now 20 years later, I know a few things to be true.

- That the average person from any village can make a massive contribution to the world if they choose to. One does not have to be wealthy or very connected or very educated (I wasn’t).

- That you choose your country – even if you were born there. Many of my friends went abroad and made a life there and many now are citizens of those countries. Those of us that live in towns and villages in Africa, must recognise that we chose to stay there.

- If you choose to stay in a place, then you must seriously contribute to its development and growth while you are there – you must find a way to be useful to it. As you do, so will your own carrier and prospects improve.

So I now am starting to make the choice to leave the city. Like 20 years ago, I had no idea what that would mean – only that I would make a difference. I had many fears and worried that I was not making the right decision. “You are crazy, Al,” I was often told. “You had a chance to live abroad and you stayed here?”

Now I am hearing similar voices. “You are crazy, Al! You want to leave the city to go live in a town? There’s no money there? Your career will die.”

There’s much I don’t know about this move. But I know this. Africa’s future is in the villages. 77% of Africans are young people who are living in villages all over Africa and they are disenfranchised because they do not see themselves as having a space in their own governance – decisions are made by old bigwigs in the city. These young people are the future and they are wasting away in villages.

What if, I wonder, we modernised and grew our villages? What if we worked with the young people and placed them at the camp of production – farming, manufacturing in the villages? What if our educated young people in the cities, moved to shags and started vertical farms in plots one-eighth of an acre? What of young people found ways to sell dried produce into the market and they could make a decent living from it, instead of being forced to go to the city to live on a pittance?

Here’s the thing, I think that a major impediment to active citizenship is the lack of a stake in the place one lives. Most young people have nothing to protect – no businesses, no livelihoods, no property. Why then should they participate in the development of their area considering that they have no ownership?

I’m thinking if young people can be more productive, they can be more active as citizens of their countries. The less they are slaves to the economy, the more they can choose to live where they do and actively participate in the governance of their areas. This is not a new idea. Years ago, I tried to figure out how techpreneurship could be encouraged in “shags” (villages). See Tech2Shags. It didn’t work at the time, but the ambition is still there.

I don’t know how that would be accomplished specifically, but I do know that I will if I spend time around them in the villages. So expect to see me spending time under trees in Malindi, Taveta or Webuye in Kenya, Amrahia or Aburi in Ghana, Serengeti in Tanzania, Koulikoro on the banks of the Niger River in Mali or Kaoma in Zambia.

That most likely will start with me moving out of Nairobi in the coming couple of years. I have significant toots in Nairobi, yes, but it will now be a secondary base for me. It was never home for me or my family, just a place to eke out a living and make sure that people in villages have a chance to find information and grow. Now, with access to high speed internet in Kenya in most places, including in the village from which I write this blog, it is possible to thrive from anywhere.

Certainly, my day job will continue and hopefully if the Safaricom internet connection I am using works well, I will be able to lead my team at the Open Institute from anywhere – something I need to learn, but that is a story for another day.

Very interesting article Mr, Al Kags, a story of Rural to Urban to Rural Migration reloaded

Nice piece Al, a great conversation starter. Now I see where Juliani got his “milioni from 10 bob” line..ha!

I share a number of your experiences and points of view… including being tagged a fool for coming back home in the early 2000s.. but home is what you make it. “Even in a desert, life is” .. I reckoned. And the encounter with the cops asking for ID (only that in my version, that is when I found out that seeing ‘stars’ doesn’t only happen in cartoons).

Leaving the city is a vibe I’m increasingly hearinbg from “xennials” as well, it will be interesting to see how it all turns out. Maybe it’s the chaos, cost and dizzying pace of this place, perhaps all the felled trees (bye, green city in the sun) and highrises, it could be the emerging opportunity back in the villages.. teach a man (or woman) to fish…, or just as you said #WFH has shown that there is really no need to be living in the city.

I recall a dream I had when I was around 5, I told my parents how I saw a factory in my shagz where cattle went in whole on one side and came out in neatly packaged beef cuts on the other. “I’ll have a factory in Kitale when I grow up”, I declared. It was all jokes then because shagz, was shagz. No power, no running water, no tarmac roads. The connection to the outside world via BBC Kiswahili at 7pm via a Sanyo radio that was powered by four size D Everready ‘Paka Power’ batteries (which had stayed out in the afternoon sun).

Yet much has changed since then, and dreams have turned into real possibilities. To me, this is ultimately what the devolution we speak about is – you, and me. 2020 may prove to be a great turning point as many people get the freedom or make the choice to work from home. And that will really show where you find your heart to be.

AL jambo we used to communicate a lot when I was in the US I am now in shags siaya

George, Its wonderful to hear from you again! Welcome home!