The murder of George Floyd, an African American man by American police has put the global focus on the police and their role in societies. Mr Floyd was killed by a white US police officer who knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes. Now there are calls in the US to disband the police force altogether and re-imagine policing anew.

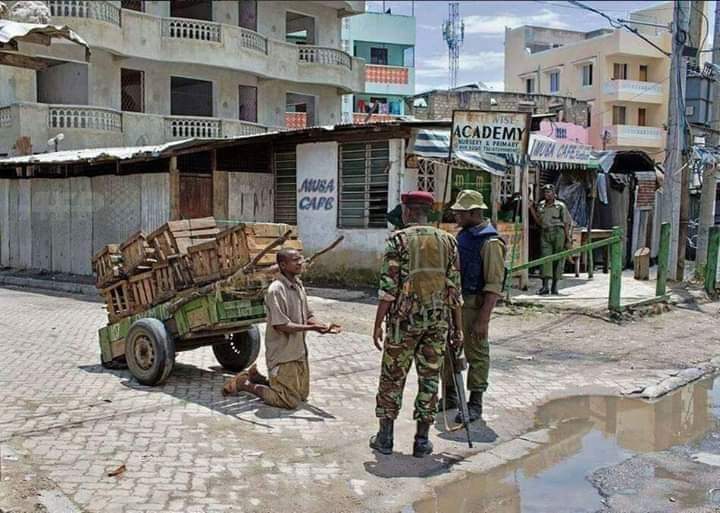

There is a need to re-imagine the police force even outside the United States. In Kenya, cases of police brutality continue to be reported in the mainstream and social media channels. Within the first 10 days of the imposition of the curfew to combat Covid-19, six people had died at the hands of the police, according to Human Rights Watch.

In a statement recently, the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) said 15 deaths linked to police action since the dusk-to-dawn curfew was put in place in late March are under investigation. IPOA has received 87 complaints about police behaviour since March 27. In addition to the killings, IPOA said people had accused police of assault and general harassment.

It is unfortunate to see the nonchalant police response to these reports, as exhibited by the Police Spokesman Charles Owino, and the studious silence of the Inspector General of Police Hillary Mutyambai.

In one case, Samuel Maina (pictured) was reported to have been severely beaten by two police officers who also robbed him. According to reports, Maina was chased from Kahawa West Police Station, where he had gone to lodge a complaint after he was branded a mad man. He went into hiding as he feared the police officers who assaulted him could identify him.

“I don’t understand why he fears for his life if he has been beaten,” said Owino. “Where did he report the matter, if he says he fears?” he added, explaining that all matters must be reported to the police if justice is to be served.

That a senior policeman cannot understand or even appreciate the fear that a brutalised citizen might have underscored the need to re-imagine our policing.

There has been little in the way of systemic change in how policing has been done in Kenya since colonial times. The structure of the police has remained largely the same since 1953 – despite changes in name.

The National Police Service (formerly Kenya Police Force) is made up of three separately-administered divisions: The Kenya Police Service, the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (formerly Criminal Investigations Department), and the Administration Police, which was created in 1958 as a paramilitary unit to “deal with matters of customary law” – that is the black African population.

This quirk of the British colonial system formalised a system that had already been in place – namely, the Home Guard system in which loyalist Africans were given special policing powers by the administration to enforce colonisation and punish dissent. They were harsher, more unpredictable and more violent than the regular police.

Change the Stance

This is the moment in history that demands that we re-imagine policing. That change would have to start with accepting that there is a problem with how the police interact with the wananchi. The rationale behind establishing community policing and change the name of the police from a “force” to “service” was meant to bring the police closer to the people. In retrospect, these changes were still cosmetic.

At the heart of the changes, what we would love to see is that the leadership within the police – with the Inspector General Hillary Mutyambai at the forefront, changing his/her stance and rhetoric to align with the people.

This would essentially mean that the leadership would express anger at seeing their junior comrades on the streets “misbehaving” (Owino’s word) instead of showing a lack of belief in the public’s fear and anguish. The power of the right words, backed up by firm action would do great things for the relationship between the police and mwananchi.

To bolster accountability and build citizen confidence, it is now technologically possible to fit every policeman with a body camera, whose retail price is as little as Sh5,000 (USD 50).

Accessible

In re-imagining policing, we would have to review how accessible the police are. Just this week, the directorate of Community Policing, Gender and Sexual Violence released a new hotline – 0800 730 999 – to report cases of sexual and domestic violence.

While this is a laudable effort, this is yet another number for us to remember – in addition to the local police station’s number, the Covid-19 number and numerous other hotlines. Kenyans have too much to remember.

In this day and age, it is entirely possible for the police to be reached by one number 999 or 911 (if we are to be so influenced by the movies) that would summon help quickly and efficiently.

What the government could do is to outsource the call centre to the many Kenyan call centres that exist in the country, with well-trained Kenyans who can professionalise police communications very quickly.

Here’s the idea more completely. It is no longer impossible or even difficult for the government to roll out a Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP)-based national network mapped to the number 999. What that would do is this: a person in Kibra would dial 999 and it would immediately be picked up at a call centre in, say, Woodley on Ngong’ Road. The dispatcher who would pick it up would be a Kibra resident who would be intimately familiar with the neighbourhood – a helpful trait given that Kenya doesn’t have a numbered street address system. It would be easier for the dispatcher to send the police to the right place and people to get help.

See also: It’s time to rethink the role of the police

Service demeanour

Of course, ultimately this would not be happening if the police do not adopt a verifiable service demeanour – that it becomes a common enough experience that the police are helpful to people. This will only be possible if the police chief and his leadership team expect and build systems to enforce polite, efficient service from the entire force.

It would also mean that the police review their hiring practices and make them consistent with how other companies and organisations do hire for most professions. You look at what you’re trying to accomplish and at what outcomes you’d like to see, then design both the duties and the characteristics of the people you’d like to hire. The major question that we must consider is this: If our goal for policing is peace and safety, why do we recruit people trained as warriors rather than as social workers?

Ultimately, the buck stops with the IG and the Minister for internal security and the President.

This article was first published in the Standard. This version has more details.