His eyes opened at 4.30 in the morning, as they had for all of the 45 summers that had passed, just about an hour or so before dawn. When he moved here 45 years ago, this neighborhood was different, quieter. It had more trees. The summer wasn’t so scathing. One could feel the ancestors still saunter around the Arroyo park area. Now, there is little silence during the summer. And the ball park across from his bedroom is filled with children, who are still free, who still have music in their hearts. Admittedly, the music was noisier, more angry in these childrens’ hearts, and they had less music in their hearts than children 45 summers ago, but they still had music.

45 years ago, he would have jumped down to the floor and pushed a hundred, followed by 75 sit ups. Now, he just lay there and waited for his legs to wake up first – that took ten minutes. Then he would slowly swing them off the bed and sit up with his legs in the slippers and wait for his back to wake up. He was used to the pains and the groaning of his old bones. 25 minutes later, he would have brushed his teeth, taken his before-food pills and put on the coffee on the same old coffee maker that he had before Sam, his last born had flown the coop. Nizzy (that is what Nizhoni, his eldest daughter, now called herself as if she was a ginger head freckled South Carolina born and bred filly), Nizzy had brought him a newfangled machine that could make “Lattes and Mochas and Capucinos” but he had no use for it. All he ever wanted was coffee, black no sugar, no cream. But she lived in San Francisco with her Italian family now and she only came around when she couldn’t avoid it. Afterall, living on the dirt road side of East Ridgecrest Drive in Flagstaff, AZ is a different world from King Street San Francisco.

“I didn’t attend the funeral, but I sent a nice letter saying that I approved of it.”

For some reason Mark Twain’s quote jumped into his head. He wondered if they would come to respectfully guide him to his ancestors. The ancestors were more his than his childrens’. Sam now lived in New York, a partner in a law firm that had 600 other lawyers. I suppose it was necessary for him to add the name Sam to his heritage name, Shikoba or he wouldn’t fit so well in his Long Island golf club. Anyway, he wondered if his children wouldn’t simply send an email to whoever was here, that they approved of his funeral as they mourned in their respective golf clubs over wine.

It doesn’t matter really. He would find his way back to his ancestors and to his Maiara. After 45 years, he had been ready to go to her a long time – certainly for these 20 since he formally became a pensioner. His children were raised and gone on to their lives, their children had grown and some had moved on to their own lives. He looked out the kitchen window and the sky was turning burgundy as the sun slowly crept up on the desert. Soon the heat would be unbearable but he was as used to it as he could be. He remembers the old ditty from the 1930s when he was a boy and smiles wistfully.

“Welcome to Arizona, where summer spends the winter — and hell spends the summer.”

As per his routine, the old man in his dark overcoat and dark shiny shoes went to the front door and opened the wooden inner door, leaving the outer glass screen door closed. He pulled the old creaking dining room chair to the door and then walked to the old Consolette turn table record player and put on the same record that he put on every day at 5.45am. He groaned as he lowered himself onto the chair.His back was more cantankerous than usual today.

“…I can make you mine

Taste your lips of wine

Anytime night or day

Only trouble is

Gee whiz

I’m dreamin’ my life away…”

As the Everly Brothers sang, he thought to himself, “I haven’t actually talked with anyone these these past three days; what bliss and what anguish.” If Maiara had been here, she would be admonishing him for it. She used to say all the time, “People are wealth. Go out and meet some.” There was this young boy who ran across the dirt road from the baseball. He cautiously crept along the path until he got to the porch and got a major fright when he found the old man there looking at him benignly. “Boy, did he run,” he chuckled. He knew what the legend was in the field these past few years. It was bound to build up. He was after all an old man who lived alone and who never came out of his house. He was the old soldier haunted by the people he had killed and there are old Indian ghosts in his house.

The boy came for three days, every day taking off as soon as he saw the old man. On the third day, he found that the old man had put on the porch, a pitcher of strawberry lemonade and a glass. “Before you run along young man,” said the old man quietly as the boy turned to run, “perhaps you can share a lemonade with an old soldier?” The boy hesitated, surprised at the gentle voice of the old fossil.

“Are you really an old soldier?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Did you ever shoot someone?”

Chuckle. “Many people.”

The boy look at him, then at the lemonade, then back at him.

“The ghosts are not here today, young man,” the old man said adding in a stage whisper, “they’ve gone south to Mexico to look for pumpkins for my soup.”

The boy was hooked. He poured half a glass of lemonade and sat at the step on the other side of the glass door. The old man did not invite him in and he felt safe with that glass door between them.

“Soup for you?”

“Yes, they take care of me. I’m too old.”

“They don’t haunt you?”

“No, they are my ancestors and they are caring for me until its time to go to their land.”

“Like guardian angels? And why they feed you pumpkin soup?” the boy asked breathlessly, rapt in the discovery.

“Exactly like guardian angels. Pumpkin soup is what friends make for each other.”

With that, the boy abruptly said his hasty thanks and took to his heels. So fast did he run that the old man imagined a cloud of dust rising up in his wake. He had to tell his friends of his discovery. Since then, the old man had spoken to no one. That was a nice respite from years of silence, which were tempered every week by Alameda, the old indian lady who came to clean for him.

As always, the old man started to dose in his chair, the sun was up and the usual activity was seen on the street. In his slumber he dreamt of Arianna, his first grandchild. She was playing on the back porch oblivious to his watching her. She looked up and said, “Old Soldier?” He smiled amused that she could speak so well.

“Old Soldier? Are you dead?” he started awake to see his young friend from the other day. He clearly was young at maybe 8 years of age.

“Not yet, young man,” replied the old fossil, “I’m still here waiting for my ancestors.”

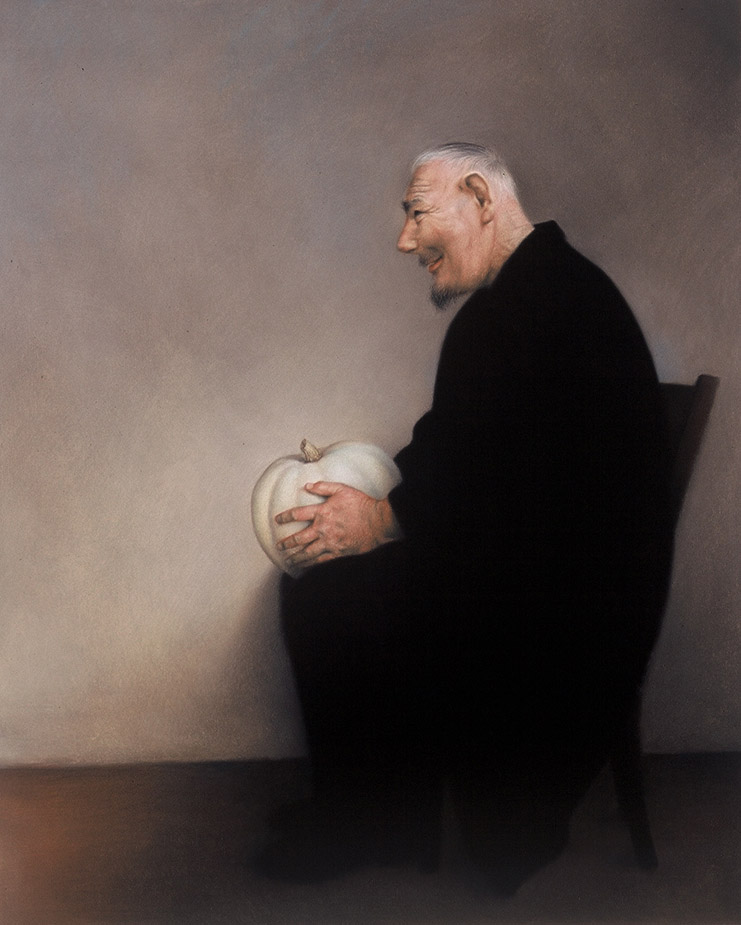

“I brought you this,” the boy thrust an obviously heavy pumpkin into his hands, “At least you can make soup before your ancestors come back.” The old man was so moved, he could not talk. “Its what friends do, right?” asked the young man.

“It sure is, young man. Thank you.” And with that the young man abruptly turned and ran out the screen door and disappeared, leaving old John with his pumpkin, a lump in his throat and a great warmth in his heart.

//Written at Arizona State University during the Washington Fellowship.

PS: I DIDN’T EDIT THE STORY SO FORGIVE THE SPELLING ERRORS.

I wrote a short story in Arizona. John With his Pumpkin. http://t.co/IcnyRCl8IW Inspired by Artist Chris Rush.

[Al Kags Officially] John with his pumpkin: His eyes opened at 4.30 in the morning, as they had fo… http://t.co/TLgbRT00ph via @alkags

I wrote a story in Arizona: John with his pumpkin http://t.co/IcnyRCl8IW

RT @alkags: I wrote a story in Arizona: John with his pumpkin http://t.co/IcnyRCl8IW

I am so happy to have finally gotten Facebook comments to work on my blog!! SUCCESS!!

John with his pumpkin: http://t.co/yX28R3uimD