The word falls effortlessly from the lips of diplomats, donors, and do-gooders alike — empower. We must empower the poor. Empower women. Empower marginalised communities. It’s a term that glitters with good intentions, polished by decades of development-speak. But peer a little closer, and you’ll catch the glint of something far older, far more uncomfortable. That shine? It’s colonial residue.

Rewind to 1884. Berlin. Otto von Bismarck gathered Europe’s great powers for a genteel land-grab. The goal: carve up Africa. Not the real Africa, rich in kingdoms like Buganda, trade routes crisscrossing the Sahel, legal codes in Timbuktu, or complex governance in the Horn. No — the Africa they conjured was a dark, blank canvas, a playground for European ambition. A continent peopled not by citizens, but by “natives.” Primitive. Backward.

Empty of civilisation — and thus ripe for it.

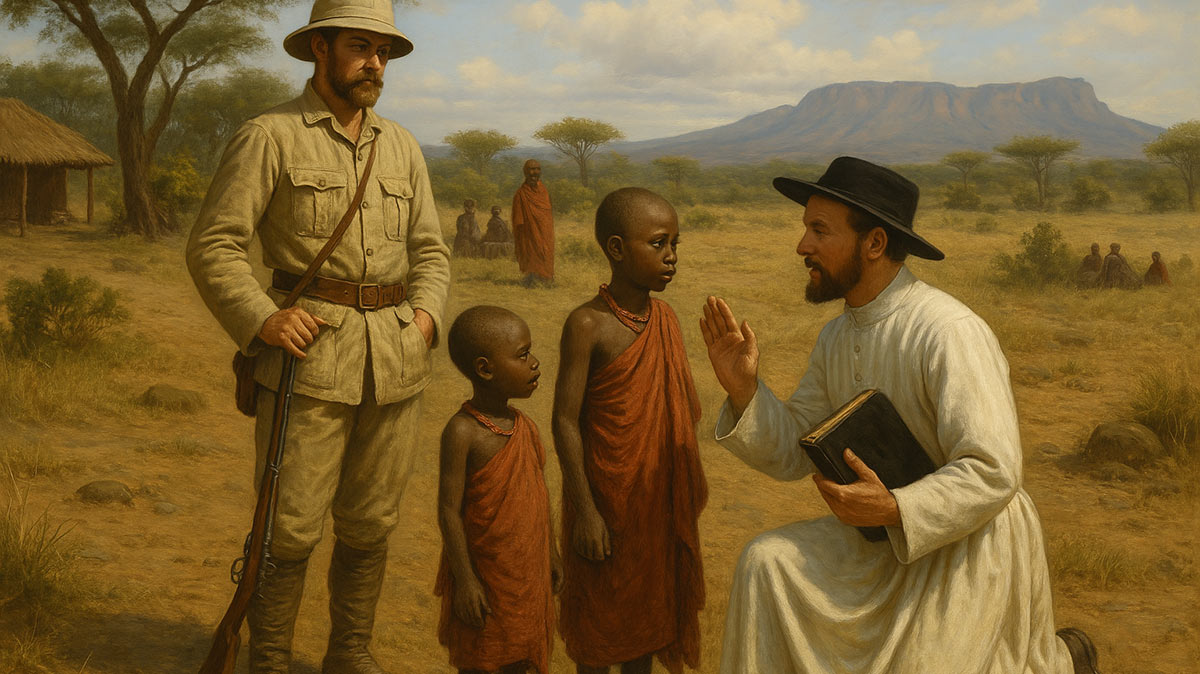

The moral alibi was elegant in its cruelty: the civilising mission.

Historian Hugh Trevor-Roper gave voice to this attitude with aristocratic contempt:

“There is only the history of the Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness… and darkness is not a subject of history.”

That wasn’t just prejudice. It was policy.

Every system that Africans had built—political, economic, spiritual—was erased or bulldozed, seen as irrelevant, if seen at all. Missionaries marched alongside administrators, holy books in one hand and Western norms in the other. To save the soul, one had to shed the self. Conversion wasn’t enough; one had to be remade.

As Chinua Achebe (left) wrote, “the white man is very clever… he has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.” The “civiliser” was not merely guiding — he was replacing.

Fast-forward to today. The Union Jack is no longer raised; instead, the logos of development agencies and philanthropic giants mark the terrain. The missionaries have been succeeded by consultants, the empire by the grant cycle. But the gaze—that enduring, intrusive gaze—has hardly shifted.

Today’s version of the civilising mission is more polite, more progressive, and printed on glossy A4 paper: “empowerment.” But at its core is the same dynamic — a one-directional flow of wisdom and resources, from those who “know” to those presumed not to.

Modern development often behaves like an overconfident tourist in a foreign bazaar — well-meaning, wallet open, but unwilling to ask directions. Entire programmes are designed in New York, Geneva, or Nairobi high-rises for communities in Lamu or Lodwar. Local realities are fitted into log frames, painted in pastel infographics, and declared “impactful.”

Like colonial officers scoffing at African governance structures, development practitioners frequently disregard informal economies, barazas, indigenous savings groups, or intergenerational knowledge systems. Like the missionaries who saw only savages in need of saving, modern aid efforts often dismiss traditional medicine, local dispute resolution, or spiritual practices unless they are first sanitised through Western metrics.

Pay attention to modern systems

Here’s a story a friend recently told me, set in rural Kenya: he and his siblings, successful and well-meaning, decided to surprise their mother with a gift — a brand-new modern kitchen. They demolished her old outdoor mud kitchen, complete with a three-stone hearth where she had always cooked using clay pots, and installed a sleek, tiled indoor one with a gas cooker and oven. Pleased with their effort, they returned to the city. Months later, they visited again — and found that their mother had quietly rebuilt her old mud kitchen outside. The modern kitchen? Used occasionally for visitors and tea. “You can’t cook ugali with a gas cooker,” she shrugged. “And where would I make mukimo? In an oven?” She had a system. They had missed the point.

That anecdote might be about kitchens, but it is also about dignity, ownership, and the quiet resistance of everyday people to being overwritten. Her values weren’t outdated; they were appropriate. Modernisation didn’t account for utility. Development missed the plot.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o called it the “colonisation of the mind” — that insidious process by which people begin to doubt their own wisdom, history, and power. Today’s development lexicon risks perpetuating this same internalised defeatism. When we speak of “capacity building,” are we truly building capacity — or are we failing to recognise it was there all along?

Because let’s be honest: what does it mean to empower someone? The term suggests they were powerless to begin with. That power is something to be handed down, not something to be recognised, supported, or simply not trampled over.

This isn’t just a semantic quibble. It’s a structural problem. Development projects built without community leadership often vanish once the funding dries up. Initiatives launched without cultural context flounder, not because the poor failed to be empowered, but because the empowered failed to understand.

As Dambisa Moyo argued in Dead Aid, billions have been spent — and often wasted — in the name of helping people who were never truly asked what help they wanted. “Beneficiaries” are not waiting in the dark for a switch to be flipped. They are already navigating complex realities — with resourcefulness, dignity, and strategies we often overlook because they don’t come wrapped in PowerPoint.

And herein lies the enduring danger of the “empowerment” narrative: it replaces collaboration with benevolent condescension. It rewards the saviour complex. It lets outsiders feel virtuous, while often excluding the very people they aim to support from shaping their own futures.

If the goal is real progress — the kind that lasts — then it’s time to abandon the saviour script. The challenge isn’t to bring power to the powerless. It’s to dismantle the systems that hoard power in the first place. It’s to make space — political, social, economic — for people to define their own development.

Real development doesn’t look like delivering solutions in briefcases. It looks like sitting under mango trees, listening before speaking, investing in ideas that don’t always come with Harvard citations but carry generations of wisdom. It looks like humility. It sounds like a partnership.

If we’re serious about justice and progress, let’s retire “empower” to the same dusty shelf where we’ve placed “civilise.” Both words share the same fatal flaw: they assume that people are empty until we arrive.

And perhaps it’s time to ask — in our development dreams, in our global summits, in our donor strategies — who exactly do we imagine ourselves to be?

Because if we keep looking at others as people who need our power, we might never realise that the ones most in need of transformation… might just be us.